John Northbourne: rebel who fled abroad and knew John Gower

• New discoveries among King’s Bench files

• Rebels fleeing abroad after the revolt

• Kent rebel served order on John Gower

A significant source of new information about the 1381 revolt in the 'People of 1381' database is the huge series of files containing the working documents of the Court of King’s Bench, the most powerful royal law court which dealt with serious cases of treason and felony and also heard a large amount of private litigation. The records of the King’s Bench were from the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries kept in the beautiful Chapter House of Westminster Abbey which was fitted out with shelving to accommodate the documents. These records were transferred to the newly built Public Record Office in Chancery Lane in 1849, enabling the famous architect George Gilbert Scott to begin the restoration of the Chapter House. Exploring the ancient Pyx Chamber beneath the Chapter House, Scott noticed that the floor was unusually springy, and realised that, mixed with rubble and other debris, were many ‘packets of ancient writs from the courts of justice’.

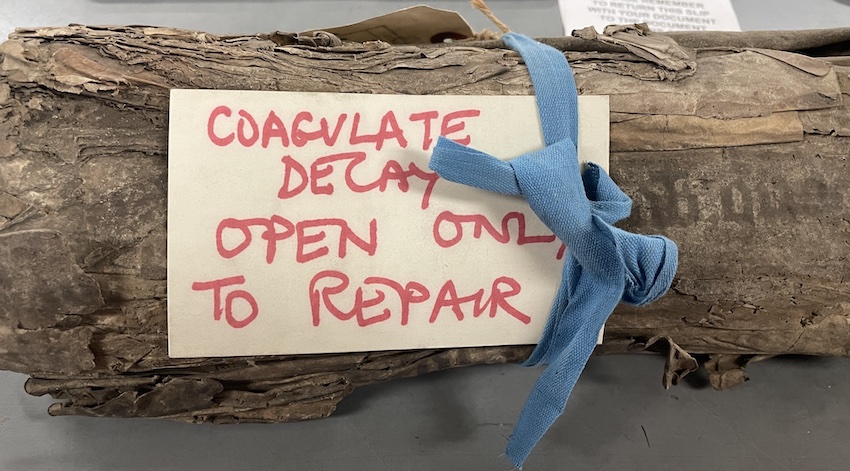

The records found by Scott were chiefly files from the Court of King’s Bench and were eventually moved to the Public Record Office between 1859 and 1861. It was assumed that most of the information in these files was already in the plea rolls, and many files remained unsorted in sacks. Various attempts were made to arrange them, but it was not until the 1960s that a concerted attempt to sort and list these files began, under the archivist C. A. F. Meekings. In one of the greatest achievements of modern archival reconstruction, Meekings recreated the King’s Bench filing system and listed the records. However, the records remain difficult to use. The files are often shrivelled and shrunk as a result of languishing in the rubble of the floor of the Pyx Chamber. In each file, dozens and dozens of documents are strung on medieval parchment thongs which could break at any moment, reducing the file to irretrievable confusion, as the following illustration of one of the King’s Bench Brevia file series (KB 136/5/6/4/1) shows:

Many of the files are in need of further conservation work, and sometimes you will encounter a stern notice from Meekings himself, like this:

Although Meekings died in 1977, there is still much to be done in arranging and exploring the files of the King’s Bench and the parallel series from the other major court at Westminster, the Court of Common Pleas. The 'Unknown Treasures' project at The National Archives recently recovered some 5,000 files of writs from the Court of Common Pleas (CP 52) which are now available for use by researchers, but there are still unopened sacks of files in The National Archives deep storage in salt mines in Cheshire. In their new article on the King’s Bench files for the Chaucer Review, Euan Roger of The National Archive and ‘People of 1381’ team member Andrew Prescott referred to ‘The Archival Iceberg’ and the files indeed suggest that much historical research today has not got far beyond the tip of that iceberg.

The potential value of the King’s Bench files has now been spectacularly illustrated by Euan Roger and Professor Sebastian Sobecki of the University of Toronto, who have discovered two documents in the Precepta Recordorum files (KB 145/3/2/2) and Brevia files (KB 136/5/3/1/2) which transform our understanding of the controversial relationship between Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne. Euan and Sebastian’s discoveries are published in a special issue of The Chaucer Review available here. This reinforces what had already been found for the study of the Peasants’ Revolt, namely that the King’s Bench files are an enormously rich but little used archival resource. The Recorda files, particularly those for 5 Richard II and 6 Richard II (KB 145/3/5/1 and KB 145/3/6/1), contain working documents relating to the prosecution of the rebels which were not copied onto the plea rolls. These include a complete roll of a commission to chastise and punish insurgents in Essex headed by Richard II’s uncle, Thomas of Woodstock, which sheds a great deal of light on the early development of the revolt in Essex, including a description of a meeting at Bocking on 2 June 1381 at which those attending ‘swore to be of one agreement to destroy divers lieges of the Lord King and his common laws and also all lordship relating to divers lords’. The roll of this commission also includes the case of John Preston of Hadleigh in Suffolk who presented a petition to the commissioners repeating the demands of the rebels at Mile End and was summarily hanged. The Recorda files also include the remarkable confession of William Delton, accused of involvement in a renewed insurrection in Kent in the autumn of 1381 which 'People of 1381' team member Helen Lacey has recently discussed in a volume of essays presented to the late Mark Ormrod. The Recorda files also contain much otherwise unrecorded information about key figures in the rising, such as the woman rebel Joanna Ferrour of Rochester and the Suffolk rebel leader John Wraw.

This new information about the revolt from the King’s Bench files is being made available to researchers for the first time via the ‘People of 1381’ database. But because the files are difficult to use and have only recently become available, new discoveries about the revolt continue to be made in them all the time. For example, work by the ‘People of 1381’ project this summer identified the following previously unnoticed indictment in the Recorda file for 5 Richard II (KB 145/3/5/1):

"John Northbourne of Kent and John Usscher of Kent were chief malefactors in the time of the insurrection of the people, namely from Wednesday before Corpus Christi [12 June 1381] when they broke the King’s gaol [carcerem regis] at Southwark and delivered the robbers and prisoners kept there. On the Thursday of Corpus Christi [13 June 1381] John and John with other malefactors of their company went to the Savoy and the place of St John [i.e. the headquarters of the Hospitallers at Clerkenwell] and there broke attacked and burnt the houses. On the following day [14 June 1381] they went to the Tower of London and helped [fuerunt adiutores] in the beheading of the Archbishop [Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury], the Master of St John [Robert Hales, Master of the Hospitallers] and others and afterwards broke the houses of Andrew Brewere [also known as Andrew Tettesworth, a brewer and notorious promoter of false lawsuits: SC 8/332/15792] at the Strand and John Botirwyk [John Butterwick, under-sheriff of Middlesex] next Knightsbridge.

And they afterwards left England and stayed across the sea [in partibus transmarinis] and now they have returned and stay in their country, that is in the county of Kent.

In the fourth year of the present King. And all this was done feloniously and treasonably in the abovesaid places on the abovesaid days and years".

This is the first reference found so far to rebels fleeing abroad after the collapse of the 1381 rising. Bart Lambert and Milan Pajic have shown how participants in the Flemish revolt of the 1340s were afterwards exiled and many were welcomed to England by Edward III. Exile does not, however, seem to have been a punishment used similarly for large-scale deportations in England. There was a procedure known as the abjuration of the realm whereby felons who had sought sanctuary in a parish church could confess their crimes to the coroner and swear an oath that they would leave the realm. The ritual of abjuration and the experiences of abjurors after they left England have been vividly described by William Chester Jordan in his book From England to France: Felony and Exile in the High Middle Ages (2015). Jordan suggests that the system of abjuration declined as a result of the Black Death and the war with France, and Shannon McSheffrey found that formal abjuration was rare by the 1390s, although it revived somewhat in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Exile was also used by the crown and parliament as a means of punishing political opponents during Richard II’s reign. Famous examples include the exile of the Bishop of Chichester by the Merciless Parliament in 1388; the exiles of Archbishop Arundel, the Earl of Warwick and Sir John Cobham by the Revenge Parliament in 1397-8; and the banishment of Mowbray and Bolingbroke by Richard II later in 1398. However, these aristocratic exiles were very different to the abjurations of criminals described by Jordan. Unlike Flanders, where hundreds were sent into exile after the suppression of Artevelde’s rebellion, few rebels fled abroad after the English revolt in 1381, and Northbourne and Usscher were unusual in seeking exile.

In heading to the continent after the revolt, it seems that Northbourne and Usscher were acting on their own initiative, taking advantage of the proximity of Kentish ports such as Dover or Sandwich. They apparently returned back to Kent in late 1381 or early 1382, and seem to have been successful in evading any responsibility for their actions during the rising. Although they were accused of participation in the killing of Sudbury and Hales and the attacks on the Savoy Palace and the Hospitallers at Clerkenwell, they were not named among those excluded from the general amnesty granted in November 1381. Neither Northbourne or Ussher seem to have received pardons for their role in the revolt. Their short self-imposed exile after the rising seems to have enabled them to avoid any retribution. A John Ussher appears in the Medieval Soldier database undertaking naval service in 1388 but this is a common name so we cannot be sure it is the man accused of joining the revolt.

But this is not the end of the story. It appears that John Northbourne knew the poet John Gower whose poem Visio Anglie notoriously portrays the rebels as monstrous beasts possessed by a savage and inhuman rage. John Gower first appears in the archival record in what his biographer Martha Carlin describes as a piece of sharp dealing over a manor in Kent. On Christmas Day 1364, William Septvans III granted to Gower the manor of Aldington Septvans in Thurnham, between Maidstone and Sittingbourne. Septvans had recently been declared to be twenty-one and Gower encouraged him to enjoy his inheritance. It was afterwards said that Septvans ‘continually dwelt in the company of Richard de Hurst and the said John Gower at Canterbury and elsewhere, and during the whole time he was led and counselled by them to alienate his lands etc.’ (Carlin, p. 27) While he was living with Gower, Septvans made further grants to Gower and others, including a grant to Gower of rents of 14s 6d in Aldington; the homages and services of the tenants of Maplescombe in Kent, together with a cock, hen and eggs; rents from the manor of Wigborough in Essex; and a bond to pay Gower £60.

However, doubts were expressed about Septvans’s real age and a further inquest was held in April 1366 which found that Septvans was only aged nineteen and not entitled to dispose of his estate. The following month the matter was brought before parliament, which decided that Septvans was clearly not yet of age, annulled all the grants made to Gower and the others, and ordered that the properties in question should be seized into the king’s hands. The sheriff of Kent was ordered on 12 May 1366 to give notice to Gower that the grants of the manor of Aldington, the homage and services (as well as the hens and eggs) at Maplecombe and the rents at Wigborough were null and void and were to be seized into the king’s hands. The sheriff returned that notice had duly been given to Gower and names the men who had given Gower notice of the seizure of the property, who were Robert Sare and John Northbourne, who seems to have been none other than the future rebel (Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem 1365-70, pp. 75-9).

Northbourne was apparently a minor member of the Kentish gentry. On the occasion of the aid for the knighting of the Black Prince in 1346, he was said to have held one quarter of a fee in Sutton, near Northbourne, from William Northbourne and the Abbot of St Augustine Canterbury (Archaeologia Cantiana 10, p. 117). He is found acting as a mainpernor in cases of debt and trespass in 1378 and 1379 (CCR 1377-81, pp. 218, 340). Northbourne is close to the port of Deal. The manor of Northbourne had belonged to the Black Prince and was used by him as a gathering point for military expeditions. John Northbourne would certainly have been able easily to hitch a ride to the continent after the revolt.

The case of the Septvans inheritance was resolved in February 1368, a few months after William finally turned twenty-one, when royal licences enabled Septvans to enfeoff Gower once more with the same properties in Kent, although not apparently the rent in Essex. In 1373, Gower transferred Aldington to a group of trustees to hold for his benefit. In the Michaelmas term of 1381, shortly after the rising, he brought a lawsuit against a carpenter, Walter Cook, over his failure to build Gower a new house at Aldington. Michael Bennett has persuasively argued that Gower was living at Aldington at the time of the rising. Aldington was close to some of the most violent incidents of the rising, such as the complete destruction of the Maidstone house of William Topcliff, the steward of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s lands. We don’t know whether Gower ever found out that Northbourne was a rebel.

William Septvans, whose estate had caused such controversy, was the sheriff of Kent at the time of the rising. When the Kentish rebels under the leadership of Wat Tyler arrived in Canterbury on 10 June, they seized Septvans and forced him to swear an oath to support them. Prisoners in his custody in Canterbury Castle were released. Tyler then forced Septvans to go to his manor of Milton where many of the records of his office were stored which Tyler ordered to be burnt. Septvans escaped without injury, perhaps because he swore an oath to the rebels. He was to be in danger again in the autumn of 1381 when a group under Thomas Harding of Linton sought to start a new rebellion and intended to seize and kill Septvans.

Juliet Barker has pointed out (England, Arise, p. 188) that there is an interesting coda to the Septvans story:

"Before [Septvans] died in 1407 he made an unusual provision in his will that, in return for their good services to him, all his servants, even those who were villeins by blood, were to be set at liberty and each of them was to be given a deed of manumission under his seal in testimony of his will".

Further Reading

Special Issue of Chaucer Review 57:4 (2022), ‘The Case of Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne: New Evidence’.

Michael Bennett, ‘John Gower, Squire of Kent, the Peasants’ Revolt, and the Visio Anglie’, Chaucer Review 53 (2018), pp. 258-82

Martha Carlin, ‘Gower’s Life’ in S. H. Rigby with S. Echard (eds) Historians on John Gower (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2019), pp. 22-120

Matthew Giancarlo, ‘The Septvauns Affair, Purchase, and Parliament in John Gower’s Mirour de l’Omme’, Viator 36 (2005), pp. 435-464.

Matthew Holford, 'Testimony (to some extent fictitious)': Proofs of Age in the First Half of the Fifteenth Century’, Historical Research 82: 218 (2009), pp.635-654

Helen Lacey, ‘Defaming the King: Reporting Disloyal Speech in Fourteenth-Century England’, in G. Dodd and C. Taylor, Monarchy, State and Political Culture in England, 1300-1500: Essays in Honour of W. Mark Ormrod (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2020)

Bart Lambert and Milan Pajic, ‘Immigration and the Common Profit: Native Cloth Workers, Flemish Exiles, and Royal Policy in Fourteenth-Century London’, Journal of British Studies 55 (2016), pp. 633-57

Adalgisa Mascio, ‘”Almost to Ruinous to Be Repaired”: The Unknown Treasures Project at the National Archives and the Court of Common Pleas Brevia Files’, Archives 53 (2018), pp. 1-11

Many thanks to Professor Martha Carlin for her comments on an earlier draft of this profile.