John Preston of Hadleigh (Suffolk) and St Osyth (Essex)

• Summarily executed because of his petition

• A martyr of the revolt?

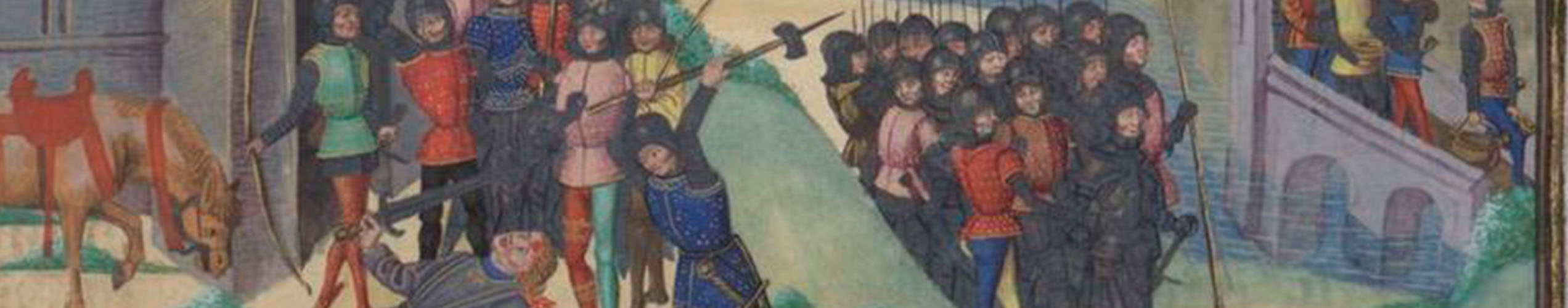

O n 25 June 1381 a discretionary commission to chastise and punish participants in the recent uprising, headed by Thomas of Woodstock, uncle of the fourteen-year-old king Richard II, held court at Chelmsford. During the session John Preston of Hadleigh in Suffolk, a tenant of St Osyth abbey, handed a written note to the justices. Addressed to the king, it read:

n 25 June 1381 a discretionary commission to chastise and punish participants in the recent uprising, headed by Thomas of Woodstock, uncle of the fourteen-year-old king Richard II, held court at Chelmsford. During the session John Preston of Hadleigh in Suffolk, a tenant of St Osyth abbey, handed a written note to the justices. Addressed to the king, it read:

' We the commons request of the special grace of our Lord the King that nobody should pay for customary land more than 4d (pence) an acre annually or 2d for half an acre ... be it with or without buildings for all services and demands ... We also request that no court should be held in any village but the leet of the Lord King annually and perpetually. Furthermore we request that if any thief, traitor or malefactor against the peace be captured in any village, you decree us a law by which he will be punished.' [KB145/3/6/1]

This is a remarkable document. Firstly, Preston’s petition not only reflects closely some of the demands in Mile End in London on 14 June, where the rebels requested from the king to be empowered to execute all traitors, that serfdom be abolished and that four pence an acre be the limit of rent for land held in any kind of tenure [Anonimalle Chronicle, 144-5; Knighton's Chronicle, 213; Westminster Chronicle, 6]. Secondly, the fact that Preston presented his letter to the justices shows the confidence people had in their cause as just, even after the rebellion had been defeated, and illustrates their absolute trust in the young king for redress. However, to hand over his petition was as ill-advised as it was bold.

Preston, who had not been indicted for any actions during the rising, was immediately arrested and questioned by Woodstock and his fellow justices. After frankly admitting that he had drafted the petition himself and it had his assent [per ipsum factam fuisse et per eum assensionem; KB145/3/6/1], Preston was summarily sentenced to death and beheaded. This was a time were words were considered as dangerous if not more dangerous than deeds as John Shirle, a 'vagabundus' from Nottinghamshire, would find out to his peril a few weeks later when he spoke highly of the recently executed ‘traitor’ John Ball in a tavern in Cambridge [JUST 1/103, m. 5; Dobson, Revolt, xxviii–xxx].

Preston’s execution triggered strong protests and led to a resumption of unrest in north-east Essex. On 27 June Lewis Chapman and John Lewys, both from Colchester, made death threats against the abbot of St Osyth and other people ‘because of the murder of John Preston’ ['pro morte Johannes Preston'; KB 145/3/6/1]. Perhaps the two Colchester men expected the abbot, as Preston’s landlord, to intervene on his behalf. During the following days several agitators rode along the coast from village to village to incite further riots and Essex only returned to relative calm at the beginning of July.

John Preston was not an ignorant and poor peasant. When the escheator Robert de Goldyngton assessed Preston’s possessions in Essex comprising livestock, cereals and wool he calculated the considerable total amount at £4 4s 2d [E136/77/1], denoting a man of substantial means. Apparently, Preston could read and write and seemed to have been familiar with the complaints of the rebels. He only did what Richard II ordered the rebels to do when they assembled at the Tower in London at the evening of 13 June, namely to go home and to put their grievances in writing [et comande qe chescune ses grevances en escript; Anonimalle Chronicle, 143]. He paid the price for following the king’s instructions with his head.

Literature:

Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333 to 1381, ed. V. H. Galbraith (Manchester, 1927).

Knighton's Chronicle 1337-1396, ed. and trans. G. H. Martin (Oxford, 1995).

The Westminster Chronicle, 1381–1394, ed. L. C. Hector and B. Harvey (Oxford, 1982).

R. B. Dobson, The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (London, 2nd edn, 1983).

H. Eiden, “In der Knechtschaft werdet ihr verharren”. Ursachen und Verlauf des englischen Bauernaufstandes von 1381 (Trier, 1995), pp. 287–8 , 395, 398, 417, 468.

Andrew Prescott, 'Writing about Rebellion: Using the Records of the Peasants' Revolt of 1381', History Workshop Journal 45 (1998), 1-27 (13-15).

Andrew Prescott, 'The Yorkshire Partisans and the literature of popular discontent', in E. Treharne, G. Walker and W. Green (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Literature in English (Oxford, 2010), pp. 321-352 (342-3).

A. Réville, Le Soulèvement des Travailleurs d’Angleterre en 1381 (Paris, 1898), p. 226.