About the Peasants' Revolt

The late fourteenth century saw a wave of popular uprisings across Europe, including the Jacquerie in France in 1358, the Ciompi in Florence from 1378-82, and a series of revolts in Flanders. One of the largest took place in England in the summer of 1381. This rising was christened 'The Peasants' Revolt' by John Richard Green in his 1874 Short History of the English People but it was more varied in character than this term suggests. Contemporary records describe the revolt more vaguely as a 'rumour' or a 'rising in a warlike fashion'.

In 1380, a poll tax of twelve pence per adult was imposed, the third poll tax in four years. Poll taxes were resented because the poor paid as much as the rich. There was large-scale avoidance of the tax and from March 1381 commissions were dispatched to enforce payment. In April, a clerical poll tax collector in Oxfordshire was attacked. At the end of May, justices in Essex were attacked with bows and arrows. On 2 June, a large meeting was held at Bocking in Essex where rebels swore 'to destroy divers lieges of the king and his common laws and all lordship'. The rebellion spread through Essex into Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Suffolk. The Essex insurgents made contact with sympathisers across the Thames in north Kent, and, while the meeting at Bocking was taking place, Lesnes Abbey was attacked.

Although the revolt was triggered by the collection of the poll tax, it was fed by other grievances. The fitful progress of the French war and French raids on southern England convinced many people that those advising the young King Richard II were treacherous. 'The People of 1381' project will use the Medieval Soldier database (www.medievalsoldier.org) to investigate how far rebels had military experience and the extent to which the militarisation of society contributed to the rising.

The King's uncle John of Gaunt was particularly hated and, in the aftermath of the Good Parliament of 1377, many were convinced that royal officials were corrupt. There was also resentment against labour legislation controlling wages and terms of service of craftsmen and other workers introduced as a result of labour shortages after the Black Death, so that many artisans and townsfolk joined the rising. A major demand of the rebels was the abolition of labour and other services for holding land and their replacement by flat-rate rents. The rebels included not only poor serfs but also tenants with land and goods who held manorial offices. The involvement of better-off tenants reflects both their aspirations and their frustration at the demands made on them by landlords.

In Essex, the first wave of disturbances culminated on 10 June in the burning of property at Cressing Temple belonging to the Hospitallers whose Prior Robert Hales was Treasurer of England. The escheator of Essex was beheaded at Coggeshall. The records of the sheriff and escheator were ceremonially burnt. In Kent, rebels attacked Rochester Castle, destroyed houses of unpopular officials and burnt administrative records. The craftsman Wat Tyler, whose origins are mysterious, emerged as leader of the Kentish rebels. There are also references to another leader named Jack Straw, but this was probably a fictitious name.

On 10 June, Tyler led the rebels into Canterbury, where they executed prominent citizens and freed prisoners held in the castle. Tyler's men returned towards London and on 12 June camped on Blackheath, south-east of London, where they were joined by John Ball, a veteran radical priest. Priests such as John Ball and John Wraw in Suffolk played a prominent part in the disturbances, suggesting links between the rising and radical Christian egalitarianism. Some chronicles reproduce letters in English attributed to Ball which perhaps provide insights into rebel ideology, but equally may have been intended by the chroniclers to suggest heretical influence.

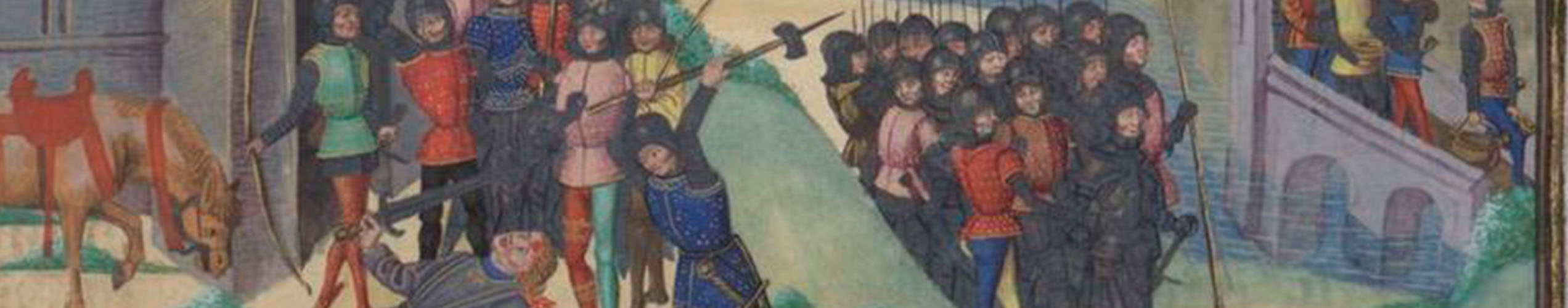

On 13 June, the King attempted to talk to the rebels from a boat at Rotherhithe. As the rebel bands approached the city, there was a huge uprising in London. John of Gaunt's Savoy palace and the headquarters of the Hospitallers at Clerkenwell were destroyed. The King met the rebels at Mile End on 14 June and gave them letters freeing them from bondage. However, rebels entered the Tower of London and seized Simon of Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor of England, Robert Hales and others, who were beheaded. There were many other massacres, particularly of Flemish merchants.

The disturbances were equally serious in East Anglia. In Suffolk, rebels led by John Wraw beheaded the Chief Justice and entered Bury St Edmunds where the Prior and another monk were killed. In Cambridge, there were attacks on Barnwell Priory and the University, while in Ely a rebel leader preached from a pulpit in the abbey and a local justice was beheaded. In Norfolk, insurgents led by Geoffrey Lister, a dyer, killed the veteran soldier Sir Robert Salle and local justices, and attacked property in Norwich and Yarmouth, where they destroyed a royal charter granting Yarmouth a much resented trading monopoly. The disturbances spread as far as Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Somerset.

On 15 June, at another meeting with the King at Smithfield to the north of London, Wat Tyler was killed by William Walworth, the Mayor of London. When Tyler fell, the King declared that he would lead the rebels and drew them away from Smithfield, averting any attempt to revenge Tyler. Commissions were issued against the rebels, and many were killed by judicial and military action in Essex, Norfolk and elsewhere. The letters of manumission granted at Mile End were cancelled. In November 1381, a general pardon was issued to the rebels, except those involved in the most serious incidents.

Although no poll tax was levied again for nearly 300 years, the impact of the revolt on such trends as the decline of serfdom is unclear. Nevertheless, it is evident from the work of authors such as John Gower and William Langland that the revolt cast a long cultural and social shadow. As late as 1413, Sussex villagers were still terrified that Jack Straw might come again.

Further Reading:

This is not a comprehensive bibliography of the revolt, but suggests some useful starting points if you would like to find out more.

Juliet Barker, England Arise: The People, The King and the Great Revolt of 1381 (London: Little Brown, 2014). A lively and authoritative narrative of the rising.

Caroline M. Barron, Revolt in London 11th to 15th June 1381 (London: Museum of London, 1981). Lucid overview of events in London and the relationship of the revolt to city politics.

Nicholas Brooks, 'The Organization and Achievements of the Peasants of Kent and Essex in 1381' in Studies in Medieval History Presented to R. H. C. Davis, ed. Henry-Mayr Harting and R. I. Moore (London: Hambledon, 1985), pp. 247-70. Detailed narrative of the outbreak of the revolt, emphasising evidence for strategic co-ordination by the rebels.

Joe Chick, 'Leaders and Rebels: John Wrawe's Role in the Suffolk Rising of 1381', Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute for Archaeology and History 44 (2018), pp. 214-34.

Samuel K. Cohn, Popular Protest in Late Medieval English Towns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012)

R. B. Dobson, The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 (2nd edition, London: Macmillan, 1983). An indispensable introduction to the rising with extensive translations of primary sources.

Christopher Dyer, 'The Social and Economic Background to the Rural Revolt of 1381' in The English Rising of 1381, ed. R. H. Hilton and T. H. Aston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 9-42.

Herbert Eiden, 'Joint Action against "Bad" Lordship: the Peasants' Revolt in Essex and Norfolk', History 83 (1998), pp. 5-30.

Herbert Eiden, 'The Social Ideology of the Rebels in Suffolk and Norfiolk in 1381', in M. Heckmann and J. Röhrkasten (eds.), Von Nowgorod bis London. Festschrift für Stuart Jenks (Gottingen: V&R Unipress, 2008), pp. 425-40. Showing how the rebels in East Anglia were as sophisticated in their ideological outlook as those in Kent, Essex and London.

Herbert Eiden, 'Military Aspects of the Peasants' Revolt of 1381', in Christopher Thornton, Jennifer Ward and Neil Wiffen, The Fighting Essex Soldier: Recruitmernt, War and Society in the Fourteenth Century (Hatfield: Essex Publications, 2017), pp. 143-54. Reviews evidence from the course of the revolt to suggest that rebels had military experience.

Sylvia Federico, 'The Imaginary Society: Women in 1381', Journal of British Studies 40:2 (2001), pp. 159-83. Discusses the involvement of women in the revolt both as participants and victims.

R. H. Hilton, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381, with a new introduction by Christopher Dyer (London: Routledge, 2003). Pioneering analysis of the social and economic character of the rising.

Steven Justice, Writing in Rebellion: England in 1381 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994). Influential discussion of the literary and cultural impact of the rising.

Helen Lacey, 'Grace for the Rebels: the Role of the Royal Pardon in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381', Journal of Medieval History 34 (2008), pp. 36-63. Key discussion of the amnesty to the rebels.

Helen Lacey, 'Defaming the King: Reporting Disloyal Speech in Fourteenth-Century England', in G. Dodd and C. D. Taylor (eds.), Monarchy, State and Political Culture In England, 1300-1500: Essays in Honour of W. Mark Ormrod (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2020). Illustrates the nature of popular political engagement.

W. M. Ormrod, 'The Peasants' Revolt and the Government of England', Journal of British Studies 29:1 (1990), pp. 1-30.

Andrew Prescott, 'London in the Peasants' Revolt: a Portrait Gallery', London Journal 7:2 (1981), pp. 125-43. Illustrates posibilities of prosopographic investigation of London rebels and their victims.

Andrew Prescott, '"Great and Horrible Rumour": Shaping the English Revolt of 1381' in The Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt, ed. J. Firnhaber-Baker and D. Schoenaers (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 76-103. Argues that the revolt was more widespread than commonly assumed and that there has been excessive attention to events in London.

Eleanor Searle and Robert Burghart, 'The Defense of England and the Peasants' Revolt', Viator 3 (1972), pp. 365-88

Paul Strohm, "'A Revelle!": Chronicle Evidence and the Rebel Voice' in Hochon's Arrow: The Social Imagination of Fourteenth-Century Texts (Princeton, 1992), pp. 33-56.

An edition of the BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time discussing the 1381 revolt, introduced by Melvyn Bragg and featuring Professor Caroline Barron, Dr Alastair Dunn and Professor Miri Rubin, is available here.

Herbert Eiden, 'In der Knechtschaft werdet ihr verharren...' Ursachen und Verlauf des englischen Bauernaufstandes von 1381, Trier Historische Forschungen 32 (Trier, 1995) is the most comprehensive narrative of the revolt yet produced and provides a perfect starting point for German readers.

On the impact of military activity on English society, the following are helpful starting points:

Adrian R. Bell, Anne Curry, Andy King and David Simpson, The Soldier in Later Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012)

Anne Curry, ed., The Hundred Years War Revisited (London: Red Globe Press, 2019)

Michael Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999)