John Spayne [Spanye, Spaygne, Spaigne] King’s Lynn, Norfolk

- New findings relating to role of King’s Lynn in revolt

- Relationship between urban and rural unrest

- Fate of people excluded from general pardon

John Spayne, a freeman of Bishop’s (later King’s) Lynn, in Norfolk, exemplifies the part played in the rising by townsmen and artisans. In the 1391 chamberlain’s accounts of Lynn, Spayne is mentioned holding a tenement in the Gresemarket area ‘the tenement of John de Spaigne, leatherdresser, on the east part’ [King's Lynn archives C48/6; KL/C50/514]. Spayne had been a freeman of Lynn since 1373/74 and is recorded as 'soutere' (shoemaker) and cordwainer [Calendar of Freeman of Lynn (Norwich, 1913), p. 20]. A cordwainer was traditionally someone who worked with Spanish leather from Cordoba; an interesting connection with John’s surname. The Spaynes might well have been an established family in Lynn: a century before John de Hispanya had been mayor. In the summer of 1381, John Spayne was repeatedly accused of being ‘a chief captain in the great insurrection (grandis rumoris) ’ by several panels of jurors in North Norfolk. However, Spayne’s exact role in the rising is ambiguous, since he was eventually pardoned on the grounds that he had been a victim of false accusation.

The rising in Norfolk is closely connected to the name Geoffrey Lister, the self-styled ‘king of the commons’, who was said to have inspired others to rise up throughout Norfolk. Lister arrived in Norfolk on 17 June 1381 and attempted to win over members of the county gentry to his cause. News of Lister’s activities may have inspired Spayne to take action in the north of the county. Insurgents from Suffolk and Cambridgeshire were also active in the area around Lynn and precipitated the disturbances there. After only a few days Lister was killed in a battle with Bishop Despenser’s army near North Walsham [Walsingham, St. Alban’s Chronicle]. Interestingly, Spayne’s pardon was awarded at the request of the same Bishop. Why Despenser chose to support Spayne’s case is intriguing, especially since he was not a man known for his clemency.

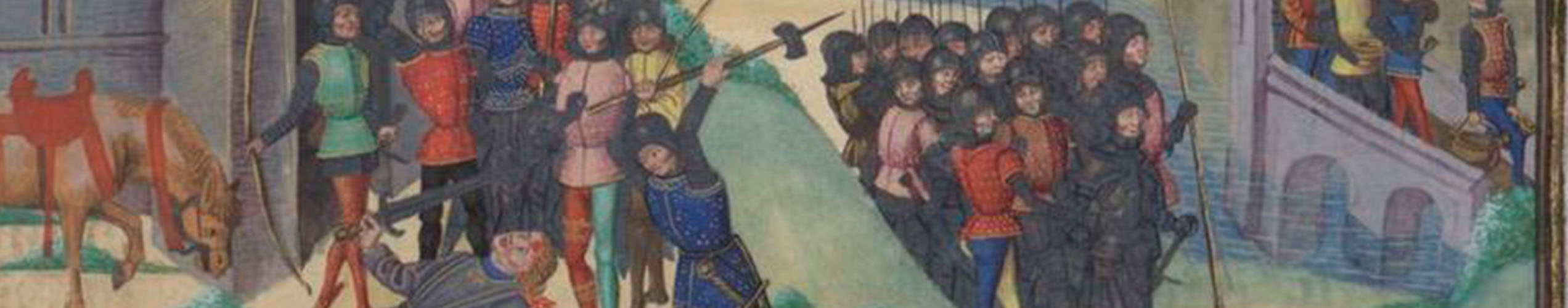

What we do know is that Spayne was accused of leading the tradesmen of Lynn in insurrection. According to the indictments, Spayne and his band travelled the local area in the period 17-22 June, extorting money through threats of violence and killing any Flemings they could find [Eiden, In der Knechtschaft, pp. 330-2]. In one indictment, they were accused of arriving at the small Augustinian priory of Peterstone in Burnham Overy (close to Holkham on the north Norfolk coast) and stealing fifteen cows from another rebel band led by Adam Calwer. This might have been the same kind of vigilante justice seen elsewhere in the revolt: Spayne returned the cows to Simon Sylk, ‘receiver’ [Reville, p. 89, n. 6; KB9/166/1, m. 80]. Spayne’s band were also said to have captured John Sybyle from Wolferton, and Richard de Walton, threatening to behead them as traitors, in direct contravention of the proclamation of the king’s peace on 18 June. Instead, after the intervention of other ‘good men’ they were released [KB9/166/1, m. 73]. However, no one intervened on behalf of their next target, a Flemish man called Haukyn, who was summarily killed by Spayne and his band. By 18/19 June, Spayne was said to have arrived in Snettisham with a band of thirty men, inciting the locals to rise up and to look for men from the country of Flanders, in order to behead them. They extorted from Simon Wylymot, (a Dutch-sounding name) 15 quarter of malt. Interestingly, Wylymot subsequently sat on the indicting jury [KB9/166/1, mm. 67, 68]. Spayne was also said to have commanded his men to kill one Ranulph Panton. Ranulph, despairing of his life, paid Spayne’s servant 10s. to be allowed free (Powell, 1896, pp. 134-5; KB9/166/1, mm. 67,68). This might have been another example of vigilante-style justice; Eiden’s research has revealed that the Panton family did not have a good reputation in the local area, having been responsible for extortion, violence and threats to local residents over a period of several years.

On 19 June Spayne was said to have moved to East Rudham, seizing Nicholas Mawpas and taking him to the neighbouring Augustinian Priory of Coxford. Nearby in Barwick, Spayne seized a vacant piece of land from Mawpas and gave it to John de Coventry, a bowmaker from Lynn. He also blackmailed Symon de Snyterton. Spayne was still active on 22 June, ambushing Edmund de Reynham (a controller for the poll tax collection) in a wood at Castle Rising and ‘fining him’ 14 quarters of wheat as ransom (Powell, 1896, p. 36; KB9/166/1, m. 73).

By November 1381 parliament was in session, and in an attempt to downplay the threat posed by the revolt a general pardon was issued to those accused of taking part [Lacey, Royal Pardon, pp. 155-8]. However, a list of 287 people to be excluded from this grace was also compiled. John Spayne’s name was on the list (PROME, November 1381, item 63). It is unclear how this list was drawn up and it seems likely that in some cases local commissions simply forwarded to Chancery the names of those against whom prosecutions were still outstanding.

By February 1383 the Commons in parliament requested that a terminal date of 7 July be set for anyone to bring private prosecutions connected with the insurrection and for the acquittal of anyone who could present the testimony of three of four worthy men. The king granted these requests in a final statute issued on 18 May 1383 [PROME, ‘Parliament of February 1383’, item 17; SR, II, 30–1]. At the same time, new judicial proceedings were initiated against those 287 individuals who had been excluded from the pardon: their names were sent to the King’s Bench and the justices accordingly issued new orders for their arrest [TNA KB 27/487, mm. 5, 6, 11, 11d; KB 27/488, m. 4].

About fifty of the 287 men excluded from the general pardon appeared in King’s Bench between 1383 and 1398, but almost all were acquitted or produced special letters of pardon granted at the request of an influential intermediary such as the queen or the mayor of London [Prescott, ‘Judicial Records’, pp. 356–7]. Spayne was one of their number: he received his pardon at the behest of Bishop Despenser on 21 May 1383 (CPR 1381-85, p. 272) and presented it in King’s Bench on 28 May 1386 [KB27/501, rex m.1d]. Spayne claimed to have been indicted ‘through the hostility of the people of the hundreds of Galhowe and Brothercros, co. Norfolk’. If this was the case then the hostility was widely felt and the jurors had been incredibly specific in conjuring up their accusations against him. Katharine Parker (UEA PhD, 2004, p. 90) has suggested that these jurors came from a region under Lancastrian influence and this, she argues, might have been the reason for Despenser’s involvement, stepping in to protect a man from a town under his jurisdiction from Lancastrian false accusations.

The accusations against Spayne demonstrate the need to reappraise the involvement of Lynn in the rising. Like Bury St Edmunds, St Albans and Abingdon, Lynn was subject to ecclesiastical lordship, in this case of the Bishop of Norwich. This had led to riots in the past and in 1377 Bishop Despenser was attacked by the townsfolk of Lynn and narrowly escaped with his life (CPR 1374-7, p. 502). However, the consensus among historians has been that, by contrast with such monastic boroughs as Bury and St Albans, there was no resurgence of early disturbances in Lynn during 1381. Kate Parker has commented that ‘When, in 1381, there is evidence for the attacks against the élite of other towns in the region, such as at Peterborough, St Albans, Bury St Edmunds, Cambridge, and Norwich, there is no record of similar disturbances in Lynn’ (in C. Harper-Bill, Medieval East Anglia, p. 122).

Despite the lack of recorded incidents in the town itself, the story of Spayne shows that there was significant support among the townsfolk of Lynn for the rising. Spayne was accused of leading a band of other traders from Lynn around the local area, attacking men like Haukyn Fleming, foreign merchants against whom they had long-standing antipathy. Furthermore, they were said to have brought at least one of their captives, John Sybyle from Wolferton, back to Lynn itself for execution. Moreover, among the named associates of Spayne were at least three men who participated in the attack of Bishop Despenser in 1377 (Thomas Colyn, a tailor, Walter Prat, a glover, and Thomas Paynot), demonstrating continuity with earlier disturbances in the town. Despenser’s willingness to secure a pardon for Spayne may perhaps reflect concern to keep the peace in his troubled lordship. While the activities of the Lynn insurgents in 1381 did not have the same urban focus as the unrest in Bury or Yarmouth, Spayne’s activities around Lynn perhaps give a more nuanced picture of the interaction between urban and rural revolt.

Spayne’s associates from Lynn:

Thomas Paynot junior, Thomas Colyn tailor, John Whetwange webster, Henry Cornysh glover, Walter Prat glover, John Snaylwell, Walter Skinner, John Bokelerpleyer, ------ Pynchebecke tailor of Lynn, ------- Sadeler staying in ‘Le Cokerowe’ next ‘Bekenhamesplace’ (KB9/166/1 mm. 73, 80, 81). Other rebels from Lynn included John Coventry bowyer (KB9/166/1 mm. 71); John Bolt (KB9/166/1 m. 79).

Link to the other excluded men whose pardons appear on the patent rolls:

| Thomas Sampson | Henry Nasse |

| John Awedyn, | Robert Wesebrom |

| Thomas Engilby | William Pypere |

| William de Benyngton | Thomas Wyllot |

| John Ellesworth | William Pykas |

| Thomas atte Raven | Robert Priour |

| Richard Redyng |

Further Reading

H. Eiden, ‘Joint Action against ‘Bad’ Lordship: The Peasants’ Revolt in Essex and Norfolk’, History 83 (1998): 5-30.

R.B. Dobson, The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (1983), pp. 231-64.

Kate Parker, ‘A Little Local Difficulty' in Medieval East Anglia ed. by Christopher Harper-Bill (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2005), pp. 115–129.

Matthew Phillips, ‘Urban conflict and legal strategy in medieval England: the case of Bishop's Lynn, 1346–1350’, Urban History 42 (2015): 365-80.