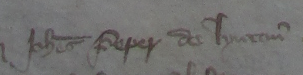

John Peper of Linton

• Can we identify rebels among lists of medieval soldiers?

• What problems will our project encounter in tracing the lives of the people of 1381?

One of the aims of 'The People of 1381' project is to use the Medieval Soldier Database (www.medievalsoldier.org) to investigate whether participants in the 1381 revolt had military experience. The case of John Peper from the village of Linton in South Cambridgeshire raises tantalising possibilities, but also demonstrates the difficulty of making firm identifications, showing the methodological issues which 'The People of 1381' will confront as its research proceeds.

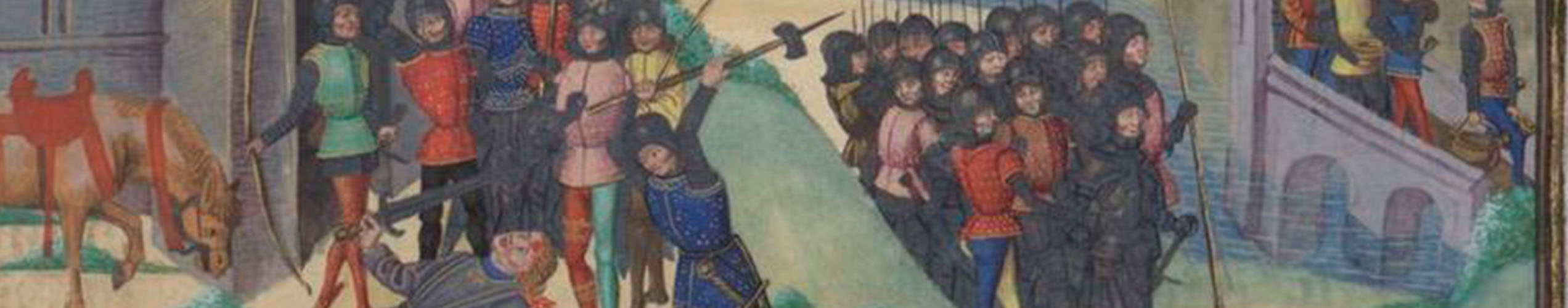

An indictment before a Cambridgeshire commission against the rebels states that John Peper rode with one of the main rebel groups in Cambridgeshire ‘carrying a lance with a pennant’ (portavit unum lanceam cum j. penoun: JUST 1/103 m. 3). The name ‘John Peper’ appears among the men-at-arms in the retinue led by Sir William Windsor as part of the expedition to France from 1380-1 commanded by Thomas of Woodstock, Richard II’s uncle. These soldiers returned to Falmouth on 3 May 1381 and it is tempting to imagine Peper riding with his lance straight back to Cambridgeshire to help raise the rebellion. However, the muster rolls do not say where Peper came from. Can we confirm whether the John Peper who served with William Windsor was also the Cambridgeshire rebel?

We are well informed about the activities of John Peper of Linton during the revolt. He was a member of the group of Cambridgeshire rebels led by John Hanchach who owned land in Shudy Camps, Duxford, Linton and other villages in south-east Cambridgeshire. Hanchach was described by Rodney Hilton as ‘at least a rich yeoman moving up perhaps into the lesser gentry’ (Bondmen Made Free, p. 181). Following a great protest meeting at Bocking in Essex on 2 June 1381, when the rebels swore to resist such injustices as the poll tax, the disturbances spread to southern Cambridgeshire. On 13 June, Hanchach led a group including men from Linton in an attack on the house of John Sibill, a Cambridgeshire Justice of the Peace, at Horseheath (JUST 1/103 m. 5d; CP 40/485, m. 247). Hanchach’s group, with Peper at the fore, then undertook a punitive raid across southern Cambridgeshire, attacking those they regarded as traitors.

Hanchach, Peper and their comrades burnt down the houses of Thomas Hasleden, the controller of John of Gaunt’s household, at Steeple Morden and Guilden Morden. They destroyed manors of the Hospitallers at Duxford and Shingay. The Order of Hospitallers was singled out during the rising because its Prior, Robert Hales, who was executed by the rebels in London, was Treasurer of England and held responsible for the government’s financial mismanagement. At Great Eversden, houses were destroyed belonging to Edward Walsingham, a local justice of the peace who was afterwards beheaded by rebels at Ely (JUST 1/103 mm. 3d, 4, 5d, 6). As they rode across the county, Hanchach and Peper ordered proclamations to be made urging people to rise up.

Hanchach and Peper arrived in Cambridge on 15 June 1381. They attacked the houses of John Blankpayn, a former mayor and MP for the town, and Roger Harleston, an unpopular land dealer who had also been an MP. The arrival of Hanchach in Cambridge precipitated attacks by townsfolk on the University and Barnwell Priory, but Hanchach and Peper moved on quickly and on 16 June they burnt down the houses of William Bateman, a Cambridgeshire JP, at Harlton (JUST 1/103 m. 4).

Hanchach was caught by a commission against the rebels in Cambridgeshire sometime in late June and was summarily executed on the orders of the head of the commission Sir Hugh Zouche (JUST 1/103 m. 3). Peper however managed to escape and his name appeared at the head of the list of those prominent rebels from Cambridgeshire excluded from the general amnesty in December 1381 (PROME, November 1381, item 63). He secured a special pardon at the supplication of the Bishop of Ely on 25 November 1383 (CPR 1381-5, p. 335) which was renewed on 20 October 1386 (CPR 1385-9, p. 232) and this pardon was then processed in the court of King’s Bench, together with letters of protection (KB 27/502 rex m. 11).

Although Peper is not a common name, there were other men with the name John Peper active at this time. One was an ironsmith who worked on Dover Castle (CPR 1374-7, p. 195; CPR 1377-81, p. 69). Another John Peper joined the retinue of the Duke of Norfolk in the Earl of Arundel’s naval expedition to Brittany as an archer in May 1388. A man-at-arms would not usually step down to serve as an archer, so we can feel confident that this John Peper is not the same as the man who served with Windsor from 1380-1. There was at least one other rebel in 1381 of the same name. John Peper of Littleport in north Cambridgeshire was accused of involvement in an attack at West Dereham in Norfolk (KB 9/166/1 mm. 46, 69).

How will 'The People of 1381' go about investigating such identifications? Can we establish whether John Peper of Linton was the man who served with Sir William Windsor in France? We will use two methods: the micro and the macro. By detailed work on Peper’s life, we can explore whether he is likely to have served in France. A macro ‘big data’ overview of the muster rolls and other records will establish whether Peper’s overall connections and associations suggest that he had undertaken military service.

The John Peper who served in William Windsor’s retinue was a man-at-arms. The social mix of men-at-arms was diverse but nevertheless ‘men-at-arms seem to have possessed, or acquired, a certain social status’ (Soldier in Later Medieval England, p. 95). John Peper of Linton would not have been out of place socially among Windsor’s men-at-arms. He owned land worth 5s per annum in Linton (E 159/159 Communia Trinity). He also had property in Fowlmere in Cambridgeshire and in 1367 was involved in a series of complex trespass cases there (CCR 1364-9, p. 391; KB 27/428 mm. 30-30d). He was able to afford the services of an attorney in the King’s Bench in connection with these cases (KB 27/428, attorney roll).

After John Peper was indicted as a rebel, the land which had belonged to him in Linton was seized, but a case in Exchequer established that Peper had granted all his lands in Linton to John Sleford and Thomas Fotheringay by a charter dated 13 January 1380 (E 159/159 Communia Trinity). The timing of this sale is intriguing and suggestive, just six months before Windsor’s soldiers set off for France. Maybe Peper was selling his land in Linton to enable him to try his luck as a man-at-arms in France.

John Peper of Linton had sufficient social substance to serve as a man-at-arms and was selling up his property shortly before Windsor’s expedition to France. But this is not enough to confirm that he served in France. This is where our macro approach may be valuable. If we can use our databases to establish patterns of involvement, links may become apparent. If a number of soldiers who had served with Windsor can also be found to have participated in the revolt. At this early stage of our research, we cannot extensively deploy this method, but there are some intriguing hints. For example, one of Peper’s associates in the revolt was Richard Cote of Badburham. A Richard Cote from Cambridgeshire had served in Calais in 1378 and it seems likely that they are the same person. Closely associated with Hanchach was John Staunford, a London saddler who also owned property in Barrington near Shudy Camps. During the revolt, Staunford rode around Cambridgeshire, carrying a deed box which he claimed contained a commission from the King to destroy traitors (JUST 1/103 m. 3d). The Medieval Soldier database reveals that John Staunford, saddler, of London received letters of protection to serve under Sir John Minsterworth in Sir Robert Knolles’s expedition in 1370.

Among the other men from Linton who joined Hanchach’s band is John Norhampton. John Norhampton was also associated with John Peper in a large and complex trespass case in Fowlmere in 1367 and they shared the same attorney (KB 27/428 m. 30 and attorney roll). Intriguingly, the Medieval Soldier database lists one John Norhampton an archer who served under William Windsor in Ireland in 1374 and 1375. Again, the identification is speculative, but the fact that two members of Hanchach’s band in 1381 share the names of soldiers who served at different times under William Windsor is striking. Was there a third party who drew both men into service for Windsor at different times? Again, this is the sort of information that may emerge during the People of 1381 project as we develop our databases.

The circumstantial evidence suggesting John Peper of Linton had just returned from military service in France immediately prior to the revolt is persuasive, if not conclusive. Peper was of sufficient social standing to serve as a man-at-arms. He had sold his land shortly before the expedition left for France. Some of Peper’s comrades in Hanchach’s band in Cambridgeshire also had military experience. Above all, the description of Peper riding through the Cambridgeshire countryside with his lance sounds like a man-at-arms in action – it was about this time that the term ‘lance’ was beginning to be used in England as a synonym for a man-at-arms (Soldier in Later Medieval England, p. 101-2).

Although we cannot firmly establish that the rebel Peper had served with William Windsor in France, our ‘macro’ overview of the Medieval Soldier database does however suggest a further line of inquiry which may settle the question. John Peper was apparently joined in France by other members of his family. The muster rolls state that Windsor’s retinue also included Hugh Peper and Robert Peper. This information may help us eventually to firmly identify John Peper.

Regardless of our final conclusions on his military service, our investigation of John Peper of Linton shows how he epitomises the complex social topography of the rising. He owned land, granted charters, engaged in lawsuits and could afford lawyers. He was one of the many rebels who were socially aspirational and apparently resented the legal and fiscal checks on their ambition.

In seeking to compare and link databases to create a ‘subaltern history’ of the Peasants’ Revolt, we have been inspired by the way such projects such as the Digital Panopticon (digitalpanopticon.org) link databases of eighteenth and nineteenth century records to reconstruct the lives of forgotten people. But, as can be seen from the case of John Peper, the linking of data derived from medieval records is more complex than for modern records. The problems include not only variable orthography and names but also inconsistencies in the structure of records and gaps in identifying individuals. Our work on 'The People of 1381' will pioneer techniques for deploying linked data methods for medieval studies.

Further Reading:

Adrian R. Bell, Anne Curry, Andy King and David Simpkin, The Soldier in Later Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013)

Adrian R. Bell, ‘The Soldier, “hadde he riden, no man ferre” in The Soldier Experience in the Fourteenth Century, ed. Adrian R. Bell and Anne Curry with Adam Chapman, Andy King and David Simpkin (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011), pp. 209-18

Juliet Barker, England, Arise: The People, the King and the Great Revolt of 1381 (London: Little, Brown, 2014), chapter 12