Margaret de Enges, Prioress of Carrow

• Carrow Road, before the football ground

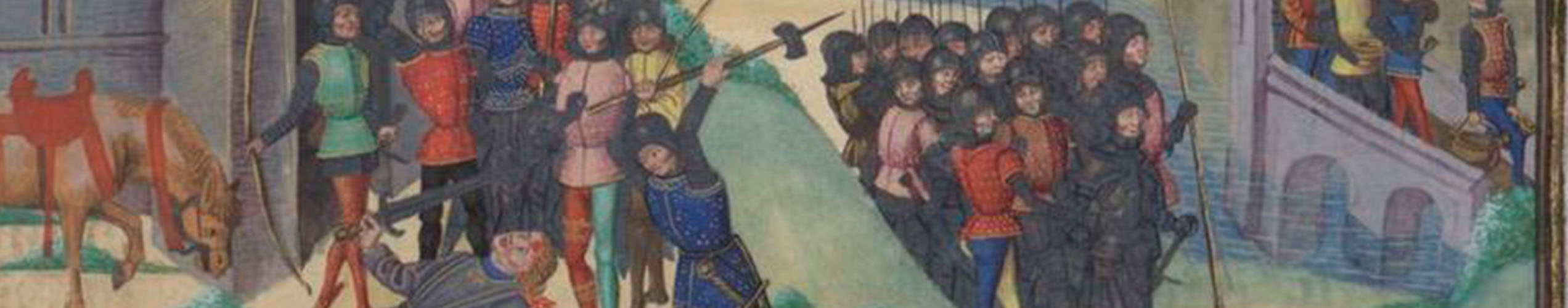

• Attacks on women in 1381

• Women initiating legal actions against the rebels

• Targeting of monastic institutions

In June of 1381 the prioress of the Benedictine convent of Carrow was a woman called Margaret de Enges [Inges/Euges]. She had already been prioress for 12 years, having been elected on 15 September 1369, and she would go on to hold the office for another 14 years, until her death in 1395. Earlier records of her residence at the convent date back to 1342, meaning that she lived at Carrow for at least 53 years, and perhaps knew the anchoress Julian of Norwich, who may have resided there in the 1350s/60s. In all that time though, Tuesday 18 June 1381 must have stood out in her memory, since it was then that she met with a band of rebels and was lucky to escape with her life.

Carrow was situated just outside the city walls of Norwich, to the south-east of the city and just a stone’s throw from the road to Great Yarmouth. On the morning of 18 June 1381 there was much rebel activity. One band of insurgents, led by Geoffrey Lyster, John de Trunch, Sir Roger Bacon and others, were en route to Great Yarmouth. At the same time, another group, seemingly composed of tenants of Wroxham manor, attacked Carrow Priory. Whether the Wroxham contingent were a splinter group of Lyster’s force, or whether they were a separate band, is up for debate. What we do know is that the rebels who attacked Carrow were led by Adam Smyth, senior, and Henry Stanford. Both men were leading tenants from Wroxham, a manor near to Norwich owned by Carrow Priory, and thus it seems likely that they were acting on a grudge they harboured against their landlord (or rather, landlady).

The description of what the rebels did once inside Carrow Priory is brief: they threatened Margaret, the prioress, with death (de vita et membris) if she did not hand over the deeds and court rolls of her house (cartas, monumenta et rotulos de curiis). Margaret sensibly acquiesced and the rebels then burned the documents in the presence of Geoffrey Lister and John de Trunch as well as other insurgents. [TNA, KB 9/166/1 m. 76, 83-6; Powel, p. 32; Réville, p. 107, n. 1.]

Two important points emerge from this description of the attack on Carrow. The first is that these rebels had few qualms about threatening elite women with violence. Elsewhere in 1381 we see women being targeted by the insurgents (although, unlike the French Jacquerie of 1358, there are no allegations of rape or sexual assault in 1381, notwithstanding the crude sexual gestures made by the rebels who broke into the Queen Mother’s apartments in the Tower of London).

The second point is that the rebels were targeting the written records of the Priory, which in their eyes symbolised the overbearing rights claimed by the priory to the detriment of their tenants. Whether or not the Wroxham rebels were a separate group, the fact that they burned the records of the priory in front of leading rebels like Geoffrey Lyster and John de Trunch, shows how their grievance against Carrow was more than a niche motivation. It seems that a distinctive feature of the 1381 revolt was that monastic houses were prominent targets: Norwich Cathedral Priory, Bury St Edmunds Abbey and several of the smaller monasteries in Norfolk alone were attacked and the Prior of Bury was famously beheaded. Whilst it was less usual for female houses to be attacked, Marilyn Oliva points out that Carrow was ‘a semi-urban monastery and holder of extraordinary jurisdiction’; as such ‘the priory was a likely target of local unrest’. Also, Carrow had the rights to one of the three major Norwich fairs [Hilton, 'Towns in English Feudal Society', p. 185] and so it could be argued that some resentment stemmed from the control Carrow exerted over Norwich's economy. By 1381, Carrow was the largest of 11 convents in the diocese of Norwich, with 27 nuns in residence. However, it was not the wealthiest, and this might have encouraged successive prioresses to push their rights as landholders to the fullest extent.

That Margaret was not cowed by the attack in June is clear; indeed, by autumn 1382 she felt sufficiently confident to bring a trespass action against the rebels who broke into her Priory, in an attempt to extract compensation [TNA, CP 40/487 m. 362d]. In this regard, the law treated her first and foremost as a landholder, regardless of her sex. Her attorney, Henry de Lesyngham, appeared against William Glovere and Henry Stanford of Wroxham, Geoffrey Hengham and John Nicole and Margaret his wife, on a plea that with force and arms they ‘broke the close’ of the Prioress at Carrow and carried away goods and chattels worth £20, together with court rolls and other muniments. The sheriff was ordered to distrain the defendants to appear in the Court of Common Pleas in January 1383 (no further record of the case survives). Interestingly, the Prioress chose to prosecute both John Nicole (Nichol) and his wife Margaret. This couple were the wealthiest of the defendants. According to the 1379 poll tax, Nichol was the farmer of the manor of Wroxham [Fenwick, 2, p. 155] and so was charged the elevated tax rate of 2s. There is also a record of a land transaction between Nichol and another leading rebel, John de Trunch, showing their connection. The Prioress may have hoped to get more damages by indicting the more affluent rebels (see a similar case in Prescott, ‘Abbey of St Benet Holme’, p. 147).

Indeed, in her time as prioress, Margaret certainly kept a careful eye on the financial interests of her convent. Only three years before the rising, in 1378, Margaret had successfully requested confirmation of certain liberties and franchises held by the convent, and letters patent were duly issued to this effect on 20 May 1378 [CPR 1377-81, p. 220]. It might also have been Margaret who petitioned the king and council for their support in a fight over jurisdiction with the prior and convent of Holy Trinity in Norwich [SC 8/101/5023, petitioned dated 1325-75 on the basis of the hand]. Towards the end of her life, in 1392, Margaret secured a sizable grant of land: ‘William Colyns and William Kilby, chaplains, and William Leverych to grant land and rent in Norwich, Lakenham, and Bracondale (Blakendele), and the reversion of land in Earlham, Trowse, Arminghall, Bixley, and Kirby Bedon, now held for life by Agnes Dowe, to the prioress and convent of Carrow, retaining land in Smallburgh and Stalham. Norfolk.’ [TNA, C 143/415/24].

The fates of some of the rebels who broke into Carrow are known, at least in part: Adam Smyth, one of two constables of Wroxham, went on to receive a pardon on 10 February 1382 [TNA, C 67/29, m. 31]. We know that the ‘rich’ rebel, John Nichol, was still alive in 1385-6, holding an estate in Wroxham and Salhouse [Norfolk Record Office 24c/13/1]. John de Trunch and Geoffrey Lyster were less fortunate; both died at the hands of Bishop Despenser in his bloody suppression of the rising in East Anglia. Margaret de Enges outlived them both by fourteen years; she died in 1395 and was buried at Carrow.

This is the site of Carrow Priory today (image: Norfolk Gardens Trust).

At the Dissolution, Henry VIII presented Carrow Priory to Sir John Shelton. The surviving building known as Carrow Abbey is an early sixteenth-century prioress's house and was the only building not alllowed to fall into ruin after the Dissolution. In the nineteenth century, the Colman family, which made its fortune from manufacturing mustard, built the enormous Carrow Works to the north and also owned the nearby Carrow House. J. J. Colman acquired Carrow Abbey in 1878 and used it to house his important library. Carrow Road was built across the Carrow Priory estate in the early nineteenth century. In 1935, when Norwich City Football Club found its existing stadium too small, it leased land from the Colman family on Carrow Road. The Carrow Road stadium continues to be Norwich City's home, and it is perhaps for this connection that Carrow is now best known internationally.

Further Reading

- A. Prescott, ‘The abbey of St Benet of Holme and the English rising of 1381’, in Monastic Life in the Medieval British Isles: Essays in Honour of Janet Burton, ed. J. Kerr, E. Jamroziak, K. Stöber (Cardiff, 2019), pp. 139-57.

- S. Federico, ‘The Imaginary Society: Women in 1381’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Apr., 2001): 159-183, p. 171.

- M. Oliva, The Convent and the Community in Late Medieval England: Female Monasteries in the Diocese of Norwich, 1350–1540 (Rochester, N.Y. Boydell, 1998), p. 29.

- M. Oliva, ‘Counting Nuns: A Prosopography of Late Medieval English Nuns in the Diocese of Norwich’, Medieval Prosopography (Spring 1995), Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 27-55.

- W. Rye, Carrow abbey, otherwise Carrow priory near Norwich in the county of Norfolk; its foundations, buildings, officers & inmates, with appendices, charters, proceedings, extracts from wills, landed possessions, founders, architectural description of the remains of the buildings and some account of the family of the present owners (England, 1889).