John Stakepoll - the First Protest Singer?

• Executed rebel named in sensational charges against London aldermen

• His goods included musical instruments

• Was he a minstrel who had been in military service?

Recently, we have been entering in our database details of the goods forfeited by those who were executed or fled after the revolt. The lists of their possessions are poignant testimony to their lives. One of the most intriguing lists of forfeited goods is that of the rebel leader John Stakepoll, who was also named in one of the most notorious and debated documents relating to the rising.

In the parliament of 1382, John Northampton, the radical Mayor of London who attacked harmful monopolies within the city, procured ordinances which severely restricted the trade of London fishmongers and barred those in victualling trades from holding office in the city. When the London fishmonger Walter Sibill protested against these measures in parliament in October 1382, one of the London MPs declared that ‘the good people of this city are strong enough to keep the peace against you all, unless you lead the commons of Kent and Essex once more into the said city, as you recently did during the treacherous uprising’. He went on to inform parliament that, according to ‘common rumour and parlance in our city’, John Horn, a fishmonger, and Adam Karlile, a grocer, had incited the rebels from Essex and Kent to attack London and had let them into the city. It was also claimed that Sibill himself had actively frustrated attempts of the then Mayor William Walworth to oppose the rebels (PROME, p. 143).

Following the heated exchanges in parliament, the Sheriffs of London were ordered by the King to investigate the allegations. The resulting two indictments taken before the London Sheriffs in November 1382 have been described as the ‘most famous and important legal records of the great revolt to survive’ (Dobson, p. 212). They allege that the city was betrayed to the rebels by a small group of five London aldermen – Horn, Karlile, Sibill, William Tonge, a vintner, and the mercer and wool merchant John Fresh, all opponents of John Northampton.

However, ever since the second of these indictments was published for the first time in 1898 (Réville, 190-6), the reliability and veracity of the charges have been the subject of much debate among historians of the Peasants’ Revolt. It now seems clear that both indictments were deliberate attempts to smear certain factions in the city and convict them of treason. The presenting juries were packed with supporters of Northampton. The first indictment was cleverly padded out with credible accusations so as to try and make the case against the aldermen more damning. The second indictment mixes information about those who undoubtedly joined the rebels such as Thomas Farringdon, a member of an old London family who was aggrieved over a property dispute, with dramatic fabrications such as the report of a speech supposedly made by Sibill who allegedly declared that ‘These Kentishmen are our friends’ and was said to have ordered that the gates of London Bridge should not be closed. As E. B. Fryde concluded ‘The two indicting juries invented happenings that never occurred or distorted the true facts … the jurors had then to fit in the partly fictitious charges into some plausible sequence of events’ (Oman, xxiii). It is the task of historians to carefully consider which of the events really occurred and who took part in them.

The accused five London aldermen were eventually all acquitted in 1384. Sibill appears in the Medieval Soldier database receiving letters of protection as an ambassador to Prussia in 1388 (Bell and Moore, p. 185 n. 15). Sibill’s mission resulted in a treaty with the Teutonic Knights, but the Master of the Teutonic Knights complained about the behaviour of Sibill, who seems to have been something of a loudmouth. One of Sibill’s colleagues on this mission was Thomas Graa, a wealthy merchant from York. Ironically, Graa supported the insurgent faction in York during the 1381 revolt (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/graa-thomas-1405).

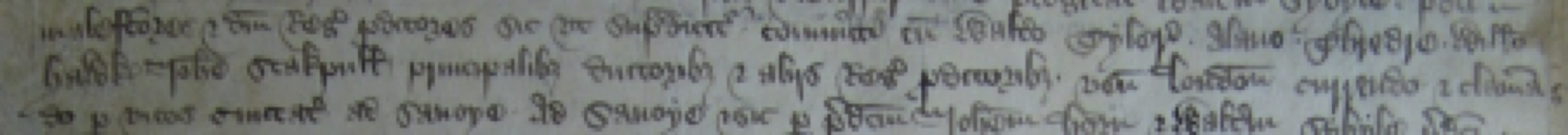

While the five London aldermen went free, there was a less happy ending for some of the other defendants in the indictments taken by the London sheriffs. One of those people was John Stakepoll. While he was not mentioned in the first indictment of 4 November 1382 [TNA KB 27/488 rex m. 6] his name is in a list of four ‘principle leaders and traitors’ (Walter Tylere, Alan Thredre, William Hawk and John Stakpull) who came to the city of London [TNA KB 27/488 rex m. 6d, illustrated below]. It seems likely that mention of his name was intended to bolster the credibility of the indictment through reference to known rebel leaders.

Stakepoll does not appear in any other indictment and we only know about his fate after the rising through an entry in the escheator accounts for Kent and Middlesex [TNA E 136/94/2]. At the end of the manuscript which covers the period from 22 July 1381 to 12 December 1382, the escheator John de Newenton accounts for the ‘goods and chattels of the traitors’ in Middlesex. He lists the property of three men, Peter Walshe of Chiswick, Thomas Bedeford, and John Stakepoll, the first two of whom had fled and been subsequently outlawed. However, John Stakepoll had been beheaded, ‘because he was one of the principal insurgents against the king’ (‘per eo quod ipse fuit unius de principalibus insurgentibus versus Regem’) on Wednesday on the eve of Corpus Christi 4 Richard II (12 June 1381).

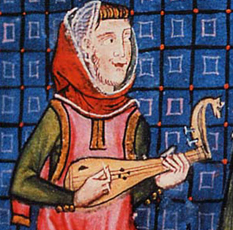

Unfortunately, neither the day when he was beheaded is noted nor when the inquisition into his property took place or where exactly he was from other than ‘Middelsex’. Stakepoll had possessions worth 18 s., consisting of a red gown (3 s. 6 d.), a cloak made of red and green cloth (8 s.), three hoods and a pair of worn out stockings (2 s. 6 d.), a pair of worn out thigh-boots (8 d.), a worn out earthen-ware pot (6 d.), as well as a harp and a gittern (12 d.).

The colourful clothes and the instruments suggest that he might have been a minstrel or another kind of musical entertainer. However, there is one more item that points in another direction: an overslop (an overgarment or cover) for a chain mail covering the head and neck (‘ventayle’), worth 18 d. Although it is a shame that the escheator did not find the armour itself it seems that John Stakepoll might have been a soldier.

A John Stakpoll served as an esquire (i.e. a non-knightly man-at-arms) in the retinue of Ralph, earl of Stafford, on an expedition into Ireland led by Lionel, then earl of Ulster in 1361, after the latter had been appointed governor of that country [TNA 101/28/15]. In 1374–5 we find him in continuous service as a man-at-arms in Ireland under the command of Sir William Windsor who was sent to the island to recover the revenues due to the English king [TNA E 101/33/34; E 101/33/35 m. 1; E 101/33/38, mm. 1,2,5]. A final record for Stakepoll’s involvement in military service dates from April 1381. It is a letter of protection to go to Brittany under the command of Sir Richard Poynings, presumably as reinforcements for the earl of Buckingham expedition [TNA C 67/65 m. 17]. However, the 2000-men strong relief troops never left Dartmouth and it has been suggested that they were sent to London on 16 June 1381 to help the government to suppress the revolt (Bell, 19). Yet, our singing soldier might have gone a few days earlier to do the opposite!

Literature:

C. M. Barron, Revolt in London: 11th to 15th of June 1381 (London, 1981).

A. R. Bell, War and the Soldier in the Fourteenth Century (Woodbridge, 2004).

A. R. Bell and T. K. Moore, ‘The Organisation and Financing of English Expeditions to the Baltic during the Later Middle Ages’ in Military Communities in Late Medieval England, Essays in Honour of Andrew Ayton, ed. G. Baker, C. Lambert and D. Simpkin (Woodbridge, 2018), pp. 181-209.

R. Bird, The Turbulent London of Richard II (London, 1949).

R. B. Dobson (ed.), The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (London, 2nd edn, 1983), 212–226.

P. Nightingale, ‘Capitalists, Crafts and Constitutional Change in Late Fourteenth-Century London’, Past and Present 124 (1989), 3–35.

C. Oman, The Great Revolt of 1381. With a New Introduction and Notes by E. B. Fryde (Oxford, 1969).

A. Réville, Le Soulèvement des Travailleurs d’Angleterre en 1381 (Paris, 1898).

B. Wilkinson, ‘The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381’, Speculum xv (1940), 12–35.