The First Eyewitness Account of the Revolt?

• Letter to Teutonic Knights describing revolt

• Earliest eyewitness report

• Who helped keep German merchants safe?

Probably the oldest eyewitness report of the rising of 1381 is a letter by the alderman and other merchants of the Hanseatic league who were present in London during the tumultuous days in mid-June 1381. It was written on Monday 17th June, only two days after Wat Tyler had been killed at Smithfield, and addressed to the order of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia. The letter, in Low German, reports that King Richard II's chancellor and his treasurer had been beheaded by people from the counties of Essex and Kent while the Hanse merchants were in hiding with their London friends and that they had not suffered a penny-worth of damage. This was in stark contrast to the Flemish, who had been chased by the rebels and several of them had been killed.

Clearly, the aim of the letter was to spread the word quickly that all Hanse merchants in London were safe and that the Teutonic Order should prevent any retaliatory measures against English merchants in Prussia by copying it and sending it to other towns in Prussia. They also wanted to ensure that international trade was flowing during this difficult time.

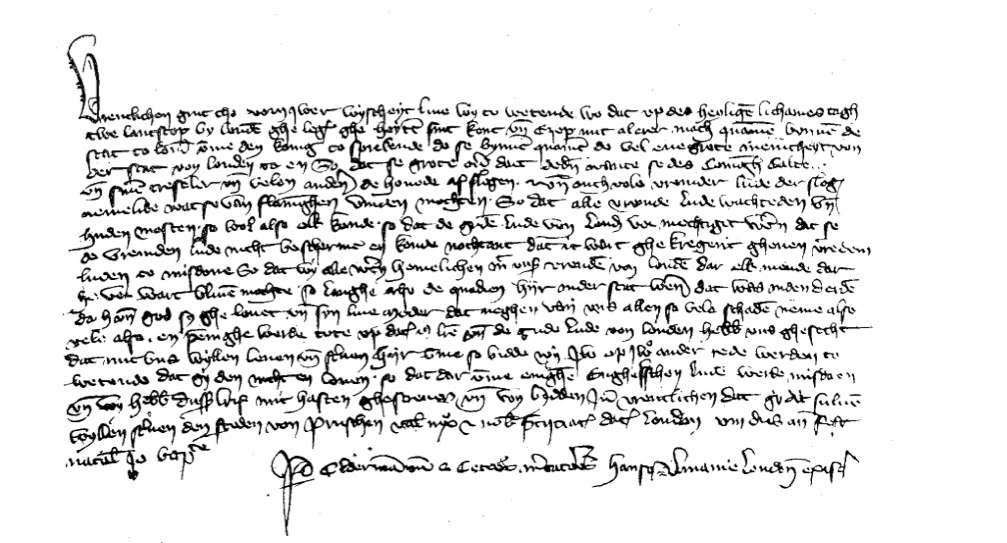

The letter, which survived in a contemporary copy, is kept in Berlin, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz [GStA PK, XX. HA, OBA, Nr. 00414]. Geoffrey Barraclough published a facsimile of the letter in 1954.

In 1984, Frederik Pedersen published an exemplary transcription and translation of the letter accompanied by a concise analysis in the Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. What probably not many readers of his article have noticed is that while the translation is complete, a line in the transcription is missing. The missing text (the last word in line eight and the first thirteen words in line nine) has been added to a line-by-line transcription followed by a revised translation:

1 Vrentlichen grut tho vorn. Iwer wyscheyt live wy to wetende wo dat up des heyligen lichamestagh

2 twe lantscope by London ghelegen gheheyten sint Kent unde Ezex mit al erer mach quamen bynnen de

3 stad to London umme den konig to sprekende. Do se bynnen quamen do vel ene grote menicheyt von

4 der stat von London to en so dat se grote overdate deden wante se des conighes calcelier

5 unde sinen treseler unde velen anderen de hovede alslogen unde ouch vele fremde lude der slogan

6 nemelike wat se van flaminghen vinden mochten. So dat alle vremden lude wachtede unde

7 huden mosten so wol also elk konde, so dat de guden lude von London vermechtiget weren dat se

8 de vremden luden nicht beschermen en konden, nochtant dat it wart ghekregerit ghenen vremden

9 luden to misdone so dat we alle weren hemelichen oner unser vrunden von London, dar elk mende dar

10 he verwart bliven mochten so Langhe also de quaden hijr inder stat weren. Dat was onden derden

11 dach unde god sy ghelovet unde syn live moder dat neghen van uns allen so vele schaden nemen also

12 vele also en penighe werde tote up datum huius littere. Unde de gude lude von London hebben uns ghesecht

13 dat mi tuns wyllen leven unde sterven. Hijr umme so bidde wy Iw op Iwo ander rede werden to

14 wetende dat gy den nicht en loven so dat dar umme enighen Enghelschen lude werde misdaen.

15 Unde wy hebben dussen brif mit hasten ghescreven unde wy bidden Iw vrentlichen dat gy dat sulven

16 wyllen scriven den steden von Pruschen. Valete in Christo et nobis precipiatis. Datum London viii dies ante festum

17 natalis Johannis baptiste.

18 Per aldermannum et ceteros mercatores Hanse Almanie London existentes.

First of all, friendly greetings. We would like your wisdom to know that on the day of Corpus Christi two counties near London called Kent und Essex came with all their might to the city of London to speak with the king. When they entered they were joined by a great number of inhabitants of the city of London so that they carried out great misdeeds as they cut off the heads of the king’s chancellor and his treasurer and many others; they also slayed many foreign people namely any Flemings they could find. Therefore, all foreign people had to be vigilant and guard themselves as best as they could. Hence the good people of London were prevented from protecting the foreign people, despite it being proclaimed that foreigners should not be harmed. That is why we all stayed secretly with our London friends, because we reckoned, we would be protected there for so long as the bad people were in the city. This happened on the third day and God and his beloved mother be praised that none of us has suffered a penny-worth of damage by the date of this letter. And the good people of London told us that they will live or die with us. Therefore, we are asking you if you should hear people saying otherwise you should not believe them, so that no Englishman comes to harm. And we have written this letter in haste and we are kindly requesting you that you should write this to the towns in Prussia. Farewell in Christ and command us. Given at London, eight days before the feast of the birth of John the Baptist.

By the alderman and the other merchants of the Hanseatic League in London.

The London headquarters of the German merchants belonging to the Hanseatic league, a powerful alliance of north European cities and towns including Lübeck, Hamburg and Danzig, was a semi-autonomous enclave on the site of Cannon Street railway station. This was known as the Steelyard, a corruption of the Low German 'Stahlhof', meaning a place where goods were offered for sale. The Steelyard developed around property granted in the twelfth century to merchants from Cologne and became the largest trading complex in medieval London. It had its own guildhall and council chamber, with shops, warehouses, wine house and a wharf. Excavations by the Museum of London in the 1980s located the remains of the Hanseatic Guildhall beneath the modern railway station. The Hanseatic merchants held generous privileges from the English crown. They paid lower custom dues and the Steelyard was controlled by a German alderman, elected from the Hanse merchants. An English alderman was also appointed by the English king and city of London, who acted as a mediator between the English and German merchants and assisted in resolution of any disputes.

The Steelyard was adjacent to the scene of one of the most notorious incidents of the 1381 rising when thirty-five Flemings who had taken refuge in St Martin's in the Vintry were dragged out of the church and beheaded. The Anonimalle Chronicle describes how the insurgents also 'took their way to the places of Lombards and other aliens, and broke into their houses, and robbed them of all their goods'. The Anonimalle Chronicle estimated that about 140 to 160 people were beheaded in this vicinity. The Hanse merchants had particular reason to feel nervous as many smaller merchants in London resented their privileges which had been revoked following the accession of Richard II. It had taken years of delicate negotiations to restore the privileges of Hanse merchants which were formally reinstated at a ceremony at Westminster in September 1380 at which Simon of Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor afterwards killed by the rebels, had presided. Tensions over the privileges of the Hanseatic merchants were still causing continued clashes at the time of the revolt, with the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights harassing English merchants and levying punitive dues on them. This doubtless explains the concern of the Hanseatic merchants in London to rapidly assure the Grand Master that they had not been harmed by the rebels and that the wealthier London merchants had protected them.

It is intriguing to wonder about the identity of the London friends who shielded the German merchants during the revolt. It is probable that William Walworth, the Mayor of London who killed Wat Tyler at Smithfield, was among those who protected the Hanse merchants. As mayor of London, Walworth had been appointed the 'English Alderman' of the Hanse in January 1381 (London Letter Book H, p. 158) and consequently had a duty to assist the Hanse merchants. Walworth's own house was close to the Steelyard, on the site of the present Fishmonger's Hall on the north side of London Bridge. Walworth may have concealed some of the Hanse merchants there although as the bridge was a scene of many disturbances, his house may have been too exposed to be a good hiding place. However, other prominent merchants such as Nicholas Brembre and John Philpot had houses in Thames Street close to the Steelyard and may have offered a refuge to the Hanse merchants during the revolt. Indeed, the knighting by King Richard of Walworth, Brembre, Philpot and Nicolas Launde after the events at Smithfield and Clerkenwell may have been as much in recognition of their bravery in safeguarding foreigners in London as their role in taking military action against the rebels.

Further Reading:

G. Barraclough, ‘The Historian and his Archives’ History Today, 4 (1954), 413.

F. Pedersen, ‘The German Hanse and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, lvii (1984), 92–8.

David Keys, 'London's German Enclave', History Today 39: 12 (Dec. 1989), 3

Plaque carved by Caius Gabriel Cibber in 1670 with the arms of the Hanseatic League and erected on a gateway on the former site of the Steelyard in London. The plaque is now in the Museum of London. For more information, see https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/118803.html