John Reed of Rougham

• New light on one of largest attacks in Norfolk

• Resentment against sheep farming fuels rebellion

Local historians have made important contributions to our understanding of the roots of the 1381 revolt. A particularly useful collection, Studies Towards a History of the Rising of 1381 in Norfolk, was edited by Barbara Cornford in 1984 and published by the Norfolk Research Committee with suport from the University of Cambridge Extra-Mural Board. Among the most valuable papers in this volume is 'The Rising of 1381 in South West and Central Norfolk' by Andy Reid (pp. 11-33) which gave one of the first overviews of the constitution and movements of rebel bands in this part of Norfolk. Andy afterwards collaborated with Barbara on a chapter on the 1381 revolt in the Historical Atlas of Norfolk published by the Norfolk Museums Service in 1994.

It was a great pleasure for People of 1381 team members Herbert Eiden and Andrew Prescott recently to meet up with Andy Reid. This profile of Andy's almost namesake, John Reed, one of the most prominent victims of the disturbances in Norfolk, was kindly contributed by him, with input from members of the project team.

John Reed was one of the people who were specifically targeted by insurgents in 1381. On 17 June, his estate in Rougham, Launditch Hundred, west-central Norfolk, was looted and devastated.

John Reed was a man on the make. His forbears, in the 13th century, had been villeins (A Jessop, The Coming of the Friars, 1888) but the family accumulated property steadily and by the middle of the 14th century the Reeds were among the leading landholders in Rougham. Along with several others, they engaged in a large number of land transactions in 1349, perhaps taking advantage of the high level of mortality in the Black Death in 1348. John Reed became the Lord of the Manor of Rougham following his marriage to an heiress, Alice de Rougham (F Blomefield, An Essay towards a Topographical History of Norfolk, 1805-10). Entries in the manor court rolls for the years leading up to and including 1381 (Norfolk Record Office, NRS 7511) show that he was relentless in asserting his manorial rights. In the same period, a sequence of acquisitions and exchanges of lands enabled him to consolidate and expand his holdings. In 1379, for example, he purchased a messuage (house) which had other messuages that he had recently purchased on each side of it (Norfolk Record Office, NRS 7370). This property lay in Westgate, an area of Rougham that was being steadily depopulated and by 1400 was ‘deserted.’ Another example involved a villein, Walter Aleyn, who found himself with land owned by John Reed on each side of his house following a purchase by the latter in 1374. In the manor court in 1379, Aleyn paid a fine to place a boundary marker between his property and Reed’s, which raises the possibility that Reed was encroaching on his land.

Sheep were an important part of the economy of Rougham and several of the inhabitants held rights of foldage which, on the evidence of the manor court rolls, were frequently disputed. That John Reed kept sheep is clear from a rental dating from around 1381, which refers to ‘the croft of the shepherd of John Reed’ (Norfolk Record Office, NRS 6493) and from the presence of a quantity of wool in his house at the time of the Rising. Reed may have been taking land out of arable cultivation to provide grazing for sheep, a process completed, probably in the early 16th century, by William Yelverton, a descendent of John Yelverton, to whom ownership of the estate had passed on his marriage to Reed’s grand-daughter.

So John Reed was an ambitious and assertive Lord of the Manor, with an expanding property holding in Rougham and an interest in the highly lucrative activity of sheep farming. His assessment for the poll tax of 1379, at ten shillings, is indicative of his wealth. Walter Aleyn’s was four pence (TNA, E179/149/53).

Reed was also a prominent figure in the administration of the County of Norfolk. He was a member of several tax commissions in Norfolk from 1377 to 1380 and became escheator for Norfolk and Suffolk in October 1381 (Calendar of Fine Rolls, 1377-83, pp. 56, 146, 188, 225, 262). He was also involved in a range of private financial dealings and was a creditor who was owed money in various parts of Central and West Norfolk (TNA, CP 40/483 mm. 439, 471; CP 40/484 mm. 353, 426; CP 40/485 mm. 44, 128).

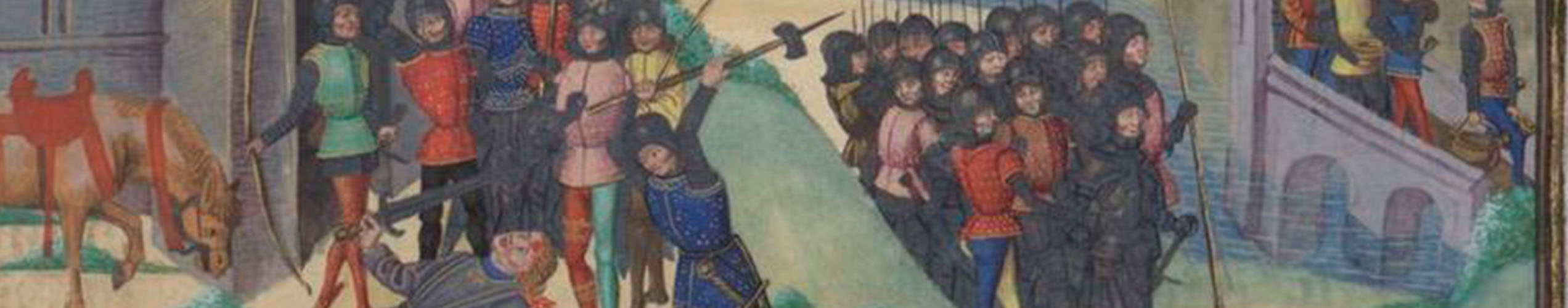

There were many people, therefore, both within and beyond Rougham, who had reasons for disliking and resenting John Reed. A large number of them came together on 17 June 1381 and comprehensively ransacked his manor house. Those involved may have constituted the largest assembly of insurgents anywhere in Central and West Norfolk during the Rising. Indictments presented by the Earl of Suffolk’s commission in the aftermath (TNA, KB 9/166/1) alleged that John Reed’s manorial buildings had been thrown down; a considerable quantity of lead had been removed from the roofs; doors and windows had been broken and their fittings taken; and a large amount of property had been looted, including an iron-shod cart, a millstone, several horses, a saddle, 16 pigs, wheat, barley, malt and wool. The total value of Reed’s losses amounted to well in excess of £50.

The insurgents assembled in Rougham included men from as far away as Wymondham, Lakenheath, Feltwell and Creake. Members of the three main rebel bands operating in Central Norfolk were present: these were a group from Thetford, Brandon and the Fen Edge in South West Norfolk, led by John and William Geldere and William son of William de Metfeld; a group from South Norfolk led by Thomas de Gyssyng; and a group from Wymondham and Central Norfolk led by John Bettes. It was resentment of John Reed’s activities at the county level, no doubt, that drew them to Rougham.

But there were also many local people involved in the events at Rougham. Four were mentioned in the indictments presented by the jury for Launditch and South Greenhoe Hundreds in July 1381. Walter Aleyn was one of them. The others were John Munnyng, Walter de Tyl (elsewhere, ‘Trille’) and John Clerk of Whissonsett, the latter not a resident of Rougham but, as bailiff to the earls of Arundel and Richmond (who both held land there) a regular visitor. Walter Aleyn and John Munnyng both appeared in the Rougham manor court rolls as capital pledges; John Munnyng regularly paid swingeing fines of several shillings for brewing and selling ale contrary to the assize and smaller ones for failing to submit it for tasting, and both he and Walter Aleyn were regularly subject to penalties for regrating (re-selling) bread. They were, therefore, tradesmen as well as small landholders. The four Rougham rebels had an accomplice from the neighbouring village of Weasenham. John Cable: described as ‘bokelerman’ (a shield man, possibly an ex-soldier, who made a living by demonstrating martial arts) and named as such in another indictment (for Gallow and Brothercross Hundreds), where he was said to have been, ‘the messenger from village to village and district to district, namely from Rougham all the way to Flegg, in order to raise the people against the peace of the Lord King in the time of the insurrection and rumour in the County of Norfolk’ (TNA, KB 9/166/1 m. 81). According to the Launditch and South Greenhoe jury, these five rebels were said to have stolen from John Reed a horse, a saddle worth 20 shillings, and other goods and chattels to the value of £20 (TNA, KB 9/166/1, m. 49). John Clerk, no doubt because of the offices he performed, must have been known across a wide area and was also indicted by two other juries, by whom he was charged respectively with stealing from Reed malt, barley and wheat worth 40 shillings and a horse and other property worth 60 shillings (TNA, KB 9/166/1 mm. 47, 80).

Additionally, no fewer than forty seven people, including the four indicted, were named as insurgents in an entry in the Rougham manor court roll for 26 September 1381. Among them were five women, one of whom was Agnes Aleyn, who may have been a relative, perhaps the widowed mother, of Walter Aleyn; she was another brewer of ale who had been hit with large fines. Also included was John Bray, petty constable of Rougham, and a member of the jury that presented the indictments for the Hundreds of Launditch and South Greenhoe; he was a brewer too. According to one of the indictments, Bray had tried and failed to persuade Walter Aleyn to swear to keep the peace (TNA, KB 9/166/1 m. 49). Perhaps he had concluded that the insurgents would be victorious and decided to join them, or perhaps the indictment reflected an effort by Bray to exculpate himself after the event. Another named was Nicholas Wryghte, who at the same court was pursued by John Reed for a debt of six shillings and eight pence.

The 47 were charged with having, ‘committed hamsoken (housebreaking) against John Reed entering his close, and carried away his goods and chattels in the time of the rumour (the rising) and similarly received the goods and chattels of the said John.’ They were punished with small fines of two or three pence, or occasionally of six pence or a shilling. Comparison with the 1379 poll tax assessments for Rougham and the rental of John Reed dating from around 1381 indicates that the 47 rebels represented the majority of the adult male population of the village. This really was a rising of the people.

The Rougham rebels may have been taking advantage of the opportunity presented by the attack on Reed’s property by people from outside the village, whose motives they may have shared. However, it also seems highly likely that their actions were driven by resentment of Reed’s conduct as landowner and lord of the manor.

John Reed survived. No doubt he was not at his residence in Rougham when it was attached; if he had been, the outcome might have been very different.

As noted above, shortly after the rising, Reed was appointed as escheator in Norfolk and Suffolk, in which capacity he presided over inquisitions on the goods and chattels of insurgents, which no doubt gave him some satisfaction. In Rougham, he continued to consolidate and extend his estate. His boundary marker notwithstanding, Walter Aleyn was persuaded to exchange his messuage for property in another part of the village (Norfolk Record Office, NRS 7376/7). In 1383, Agnes Aleyn also exchanged pieces of land with Reed (Norfolk Record Office, NRS 7387). References in the manor court rolls indicate that customary rights of way were being closed. John Reed was getting what he surely wanted: an extensive and compact holding in the western part of the village, There is no evidence of human settlement in that part of Rougham after the 14th century, but sheep there would have been a-plenty.

Further reading:

A W Reid, 'The Rising of 1381 in South West and Central Norfolk', in Studies towards a History of the Rising of 1381 in Norfolk, ed. B Cornford, 1984, pp. 11-33.

Alan Davison with Andy Reid, 'Rougham: the Documentary Evidence', in Six Deserted Villages in Norfolk, East Anglian Archaeology 44, 1988.

See also:

Herbert Eiden, ‘Joint Action against “Bad” Lordship: The Peasants’ Revolt in Essex and Norfolk’, History 83 (1998), pp. 5–30.