The 1381 Game: Choose Your Own Revolt. Revolt. Again

Among the creative outputs of The People of 1381 is a play specially written by the playwright, director and teacher of creative writing Poppy Corbett, who has worked closely with the research team from the project. Poppy's play, The Time of Rumours, was developed with students from the Department of Film, Theatre and Television of the University of Reading. The play will receive a reading at the Essex Book Festival event at Cressing Temple on 25 June 1381.

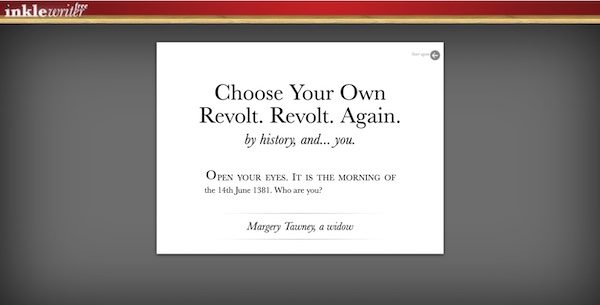

While working with the students at Reading, Poppy developed an online game about the 1381 revolt, Choose Your Own Revolt. Revolt. Again. You can play the game by clicking on the image below. This will open the game in a new window - close the window to return to this page.

Poppy has provided the following notes for you to think about as you navigate your way through the different twists and turns of the game:

This is an online game about a real person the historians found in the archive: Margery Tawney [Tany]. I made it online using ‘inkle studios’ free online game-writing software. [inklewriter.com].

You can find out more about Margery on the project’s website, but try not to read it until you have played the game, as knowing more will affect the way you play.

You can also find attached some information about Margery, and about questions I asked the historians when I made the game, and responses they gave after testing the game out. Again, try not to read this until you’ve played the game at least once, as it will affect the way you play.

Lots of the facts in the game are ‘true’, though much is invention.

Rules for playing:

Read the text and use your cursor to click the options at the bottom of the screen. On the first page there is only one option, ‘Margery Tawney, a widow’. Click that to begin the game.

If you click an option, and it says ‘End’ in the bottom right corner, after the story text, it means that your story is over. You can click the top right grey arrow in a circle, which says ‘Start again’ in small grey letters next to it. This can take you back to the beginning, or to a previous section, to start playing again.

Key points:

I’d like to highlight three important aspects of the game:

1. It is the story of a woman caught up in the revolt. Sylvia Federico has written that women in 1381 are “overlooked and ignored by the scholarship, their presence in 1381 is assumed to be unreal” (p.159). Ever since Dr Helen Lacey described Margery’s story to me, I knew I wanted to explore her story in some detail. “Because why have our stories been ignored? For so long. Ask yourself why”, asks the character of Emilia in Morgan Lloyd Malcolm’s play, Emilia, a play which posits that question (p. 75). Stories of women in history have been marginalised, and it has always been important in my historical creative writing to try and centre their experience, where possible.

2. The game uses the pronoun ‘you’. This is deliberate. Playing a game is theatrical. (Remember, a play is play…!) By using the pronoun ‘you’, I wanted to draw the player closer to Margery’s story, asking what might be learned about historical people through engaging with history as a performative experience, beyond an understanding of facts and figures. Game-playing relies on some degree of immersion, and a refiguring of the self in relation to the character you play. I hoped that rather than just reading a history book, at some distance from the past, playing a game, as figure from the past could lead to an emotional, and affective understanding of it. You make decisions as Margery, and these choices determine her story. I’m not an expert on gaming literature, but several academics have explored this area in detail, which may be interesting for you to research further.

3. The experience of the game reflects the dead ends, and small fragments of the archive. When I worked on the creative/historical project ‘Creative Histories of Witchcraft’ at the University of Bristol, my colleagues (Dr Will Pooley, a historian, and Anna Kisby, a poet) and I discussed what turning history into games might ‘do’ to that history. We had a sense that a ‘choose your own adventure’ style game might lend itself to the randomness and fragmentation of writing history. I’m glad I’ve had the chance to make one on this 1381 project.

I’d always enjoyed ‘choose your own adventure books’ when I was younger. When I found this software to make this game, I knew I wanted to try it out. It works through choice and chance. To me, this is important – history is made through moments of choice and chance. If someone had behaved in a slightly different way, their future (and the world’s future) may have radically altered. To highlight this, in the game there are small moments that I have randomized, so if you play the game several times, you might notice something changes. (What someone eats for example.) On the inklestudio webpage, it describes how to do this when making a game.

There are also lots of dead ends in the game – these are frustrating, as you have to return to earlier on in the game and play everything again. In some way, the experience of making (and I hope playing) the game captured my belief that history is shaped, mediated and constructed. History is storytelling. It is not a fixed entity that can be easily grasped. (Some historians may differ from me in this belief!) History, is also, always changing and updating, and therefore very frustrating.

Questions to ask yourself when playing:

- What choices are you making and why?

- Are you deliberately making choices that you think may be historically ‘correct’?

- Are you deliberately making choices that you think may be historically ‘incorrect’?

- Are you trying to make Margery’s life harder, or easier for her?

- How does being referred to in the second-person, ‘you’, make you feel?

- What do you think you’ve learnt from playing the game about the rebellion? How do you learn whilst game-playing?

- Which moments visually / intellectually stand out for you?