Westminster and St Mary Pew

• Did Richard II dedicate England to the Virgin Mary during the revolt?

• Did Richard II dedicate England to the Virgin Mary during the revolt?• Memories of 1381 invoked as the COVID-19 pandemic takes hold

• Central role of Westminster Abbey at a time of crisis

A recent issue of Vatican News reports how on 29 March 2020, as restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in England, Roman Catholics and other Christians offered prayers to re-dedicate the country to the Virgin Mary. You can read the Vatican report here: https://www.vaticannews.va/en/church/news/2020-03/england-dowry-mary-dedication-richard-walsingham.html.

According to the Vatican, this re-dedication of England to the Virgin at a time of great crisis harks back to the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 when (so the Vatican claims) King Richard II made a series of 'entrustment vows' dedicating his country to the Virgin Mary during a visit to Westminster Abbey immediately before the meeting at Smithfield at which Wat Tyler was killed. What evidence do we have for these 'entrustment vows' and how did this tradition arise?

The idea that England was cherished and protected by the Virgin Mary and that she had an interest in its ownership in the same way that a bride had rights in land given to her on marriage as a dowry is first mentioned in the middle of the fourteenth century, but is perhaps older. In about 1350, the mendicant preacher John Lathbury declared that 'it is commonly said that the land of England is the Virgin's dowry' (Saul, p. 208). Edward III encouraged this identification of England with the Virgin in order to foster his claim to the French throne.

It became customary to refer to England as the Virgin's dowry at times of crisis and when appeals were made for unity. In February 1400, following Henry IV's seizure of the English throne and the suppression of a rising against him, Archbishop Thomas Arundel enjoined devotion to the Virgin and declared that the English were 'humble servants of her inheritance and bondsmen of her especial dower' (peculiaris dotis ascriptii: Wilkins, Concilia, iii, pp. 246-7). According to Thomas Elmham, on the eve of the Battle of Agincourt, priests with Henry V's army asked the Virgin to bestow her favour on the English 'as your right dowry' (Curry, pp. 46-7).

Richard II was one of the most enthusiastic promoters of the idea that England was the Virgin's dowry. The celebrated Wilton Diptych in the National Gallery, executed between about 1395 and 1399, shows Richard kneeling and presenting a pennant to the Virgin. The pennant is decorated with the cross of St George and at the top of the staff is a tiny map of an island which probably represents England and refers to the idea of England as the dos Mariae, the dowry of Mary. An altarpiece in Rome, now lost but described in the seventeenth century, showed Richard II and Anne of Bohemia offering the island of Britain to the Virgin with the inscription 'This is your dowry, O Holy Virgin, wherefore O Mary, may you rule over it' (Gordon, 1992, pp. 665-6).

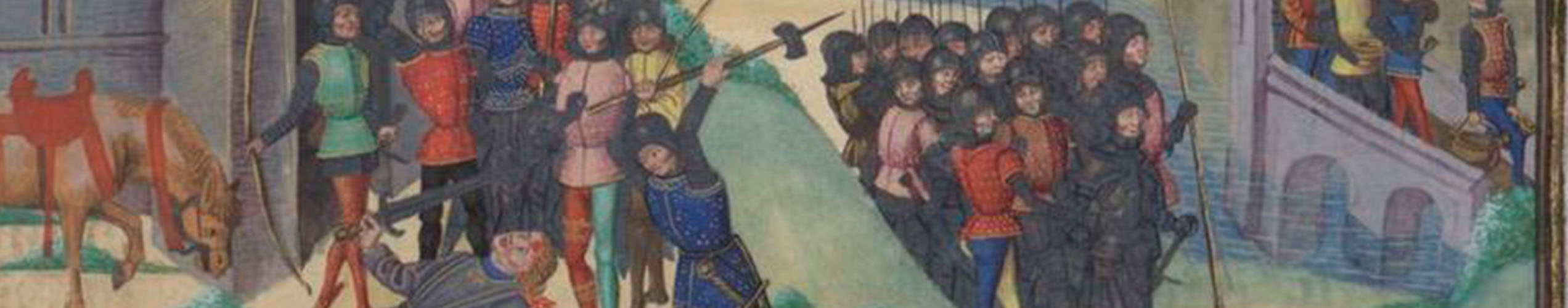

It was to the Virgin that Richard turned at the height of the rising in 1381. On Friday 14 June, Richard met the rebels at Mile End and gave them charters of manumission, but the Tower of London was nevertheless seized and senior royal advisors, including Simon Sudbury the Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor of England and Robert Hales, Prior of the Hospitallers and Treasurer of England, were beheaded.

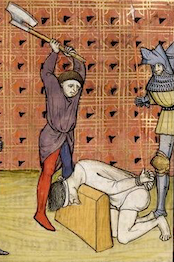

Richard stayed that night at the Great Wardrobe building near Blackfriars, where his mother had also taken refuge (Dobson, Peasants' Revolt, pp. 162-3). Early on Saturday morning, Richard led a 200-strong procession to Westminster Abbey. This was a courageous move, since the abbey had already been the scene of much violence. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle, after Sudbury, Hales and other officials had been beheaded, the rebels had 'processed' to the shrine of Westminster Abbey, holding aloft the heads of those they had killed on wooden poles. This macabre procession was perhaps a parody or inversion of the kind of penitential processions or pilgrimages that were familiar to the insurgents. In another incident within the abbey, rebels seized Richard Imworth, the official in charge of the prison of the Court of King's Bench, described by the Anonimalle Chronicle as a 'tormentor without pity'. According to the Westminster Chronicle, Imworth clung on to a marble pillar at the shrine of St Edward the Confessor, 'hoping for aid and succour from the saint to preserve him from his enemies', but he was nevertheless dragged out of the abbey and beheaded.

As the King led his procession to the abbey on the morning of Saturday 15 June, the Abbot and Convent and the canons and vicars of St Stephens chapel came to greet him. (The Anonimalle Chronicle places this meeting at Charing Cross, but the Westminster Chronicler says they met at the door to the Abbey, which is surely more likely). They were 'clothed in their copes and their feet bare' (Anonimalle Chronicle) and they led the king to the high altar.

Accounts differ as to what Richard did next. The Westminster Chronicler suggests that the king prayed at St Edward's shrine and left offerings, adding an element of competitive piety: 'you could see lords, knights, esquires and many others strive among themselves in pious devotion as to who should make the first offerings to the relics of the saints resting there and who should shed the most tears while they prayed'. The same chronicler states that Richard then spoke to the abbey anchorite. This was John Murimouth (d. 1393), a senior monk of the abbey who lived in a cell with a window overlooking St Benedict's chapel. Murimouth probably entered his secluded existence when King Richard was crowned in 1377, and it was Murimouth who established a tradition whereby the Westminster anchorite was regarded as an oracle whose advice was sought by kings and nobility (Peers and Tanner, pp. 155-60).

According to the French chronicler Jean Froissart, who may have derived his information from a member of Richard's entourage, perhaps William Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury, Richard then went to pray privately. Froissart explained that 'In that church there was an image of the Virgin in a little chapel which did great miracles and in whom the King of England always placed great confidence and trust' ['En celle eglise a une image de Nostre Dame à une petite cappelle, qui fait grans miracles et grans vertues, en lequelle li [roi] d'Engletière ont tousjours eu grant confidence de creance']. The King prayed before this image and made an offering to it, then leapt on his horse and made his way to meet Tyler at Smithfield.

It is Froissart's report of Richard's praying to the image of the Virgin which forms the basis of the claim that Richard made vows entrusting his kingdom to her before the fateful meeting at Smithfield. However, neither Froissart or any other chronicler suggest that Richard made any vows. All we know is that he prayed privately. Can we say any more about the statue of the Virgin to which Richard was so devoted?

It seems likely that Richard made his prayers in a small side chapel next to St Stephens Chapel in the Palace of Westminster. This was known as the Chapel of St Mary le Pew because it originated as a room containing the private pew where the king sat during services. Edward III refurbished the royal pew as a private oratory and gave pride of place to a splendid jewelled statue of the Virgin which had been owned by Henry III and specially bequeathed by him to Edward I. Edward III claimed that this statue had miraculously protected him: 'when we have been cast in many kinds of dangers has protected us heretofore with her prayers and cherished us with all good fortune like a better mother' (Hastings, p. 77). By moving this figure into the royal pew, Edward III was emphasising its association with the English crown (Hastings, pp. 74-5).

Elizabeth Biggs in her study of St Stephen's Chapel notes how this image of the Virgin was already a popular place of pilgrimage by 1356. It was probably here that Richard prayed in 1381. The reference in the Anonimalle Chronicle to the canons of St Stephens meeting the king seems to confirm that Richard intended going to St Stephens. Moreover, this chapel in the Palace of Westminster was more easily screened from external intruders at a time when the area around the Abbey was in uproar. The devotional popularity of this chapel is apparent from the fact that in 1393 thieves stole 500 marks in jewels which had been offered to the Virgin there (Westminster Chronicle, p. 513).

However, there was also another chapel of St Mary le Pew at Westminster which was immediately adjacent to the Confessor's shrine. It was probably established by the monks of Westminster in annoyance at the popularity of the image in St Stephen's Chapel as a site of pilgrimage. In 1377, an alabaster statue of the Virgin had been bequeathed to this chapel by the Countess of Pembroke in memory of her husband. This chapel was afterwards decorated with Richard's symbol of the White Hart and it has been suggested that a small ledge in the chapel was one of the places at which the Wilton Diptych was displayed. It is possible that Froissart was referring to this chapel in his description of Richard's prayers before Smithfield, but the chapel in the abbey was a relatively new creation. The chapel of St Mary le Pew attached to St Stephens, with its image of the Virgin venerated as a protector by kings of England back to Henry III, fits Froissart's description much better and it was probably in the chapel of St Mary le Pew attached to St Stephens Chapel that Richard prayed before he went to met Wat Tyler at Smithfield.

Richard evidently felt that this statue had once more demonstrated its power by protecting him during the 1381 Revolt. Richard's assumption of a special affinity with the Virgin was powerfully expressed in the Wilton Diptych which was perhaps intended for use in the royal chapels at Westminster. If Richard's experiences during the revolt and the dramatic events at Smithfield affected his subsequent view of kingship, it was to a large degree because of this sense that he was protected by the Virgin. This concept of a special connection between the English crown and the Virgin was taken over and developed by the Lancastrians.

However, there is no evidence to support the claim by the Vatican that Richard made 'entrustment vows' to the Virgin in 1381. The conjecture that in 1381 Richard entrusted his kingdom to the protection of the Virgin was part of an invention of tradition by English Catholics which reached its culmination in the re-dedication event in March 2020.

After the Reformation, exiled English Catholics fostered the memory of England as Mary's dowry. At the English College in Vallodolid in Spain there was a picture showing English Jesuits under the protection of the Virgin with the inscription Anglia dos Mariae (England, Mary's dowry) (Shell, p. 206). In 1651, the English Jesuit Edward Worsley referred to 'the most Blessed Virgin, Mother of God, whose Dowry our own now distracted country was sometimes not undeservedly stiled, both in respect of the peculiar devotion our religious predecessors, above other nations of the Christian world, bore towards her, and her reciprocal procuring, by her powerful intercession, innumerable select favours for them' (Bridgett, p. vii).

Following the reestablishment of a Catholic hierarchy in England in 1850, Marian devotion was seen as vital for the re-conversion of England. Cardinal Newman in his Second Spring Sermon in 1852 called on Mary 'to go forth in thy strength into that north country, which once was thine own, and take possession of a land which knows thee not'. In 1875, the Redemptorist historian Thomas Bridgett published a book documenting English devotion to the Virgin called Our Lady's Dowry: or How England Gained and Lost that Title which ran to three editions and popularised among Victorian Catholics the idea that England in the middle ages had a special relationship with the Virgin. It included the tale of Richard praying in the chapel of St Mary le Pew during the revolt, suggesting that Froissart had confused the two chapels and that Richard prayed in the chapel attached to St Stephens chapel (Bridgett, pp. 315-6). Another Catholic apologist and antiquary, Edward Waterton also repeated the story in his Pietas Mariana Britannica, published in 1879 (p. 234).

In February 1893, the Duke of Norfolk led a national pilgrimage to Rome, where the Pope in his response to the address of the English pilgrims referred to the tradition of England as Mary's dowry and proposed a consecration of England to both the Mother of God and St Peter. The idea of a national consecration had a precedent in the legend that Louis XIII had consecrated France to the Virgin in 1638 and the enthusiasm among French Catholics that the country should be dedicated to the Sacred Heart.

This act of dedication of England as Mary's dowry took place at the Brompton Oratory in 1893, and Thomas Bridgett was selected as the preacher. In his sermon, Bridgett more firmly linked the origin of the dowry to Richard's prayers before the meeting in 1381. Bridgett claimed that England was definitely granted to the Virgin during the reign of Richard II. In answer to the question 'At what time, then, or from what motive, did Richard Make over England to Our Lady as her dowry?', Bridgett responded: 'To this I can only answer by conjecture; but it will be in accordance with every known fact if I assign 1381 as the year, and as the occasion the almost miraculous deliverance of the young King, after imploring Our Lady's help, from the hands of the rebellious peasantry' (The Tablet, 1 July 1893, p. 9). Bridgett's twice repeated caution that the claim that Richard entrusted his kingdom to the Virgin as her dowry in 1381 was 'only conjecture' has generally been overlooked, and most assumed, in the words of Bridgett's biographers that he had 'unearthed the origin, and with it the true meaning, of the title of Our Lady's Dowry'.

King Richard certainly subscribed to the concept of England as Mary's Dowry, as is evident from the Wilton Diptych, and both of the chapels named for St Mary le Pew at Westminster were closely connected with this cult, but to go from this to claiming that Richard made entrustment vows in 1381 is a conjecture too far.

Further Reading:

Elizabeth Bigg's superb new book, St Stephen's College Westminster: A Royal Chapel and English Kingship 1348-1548, just published by Boydell and Brewer, includes a wealth of information about the Chapel of St Mary Pew: https://boydellandbrewer.com/st-stephen-s-college-westminster.html

E. Biggs, 'Richard II's Kingship at St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster, 1377-1399' in G. Dodds, ed., Fourteenth-Century England X (Woodbridge, 2018)

T. E. Bridgett, Our Lady's Dowry; or, How England Gained and Lost that Title, a Compilation (London: Robson, 1875)

Anne Curry, The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2000)

Dillian Gordon, 'A New Discovery in the Wilton Diptych', Burlington Magazine 134 (1992), pp. 662-7

Dillian Gordon, with Caroline Barron, Ashok Roy and Martin Wyld, The Wilton Diptych (New Haven: Yale, 2015)

Maurice Hastings, St Stephen's Chapel and its Place in the Development of Perpendicular Style in England (Cambridge: University Press, 1955)

Cadoc D. A. Leighton, Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 1854-1893', Journal of Religious History 39:1 (March 2015), pp. 68-85

Charles Peers and Lawrence Tanner, 'On Some Recent Discoveries in Westminster Abbey', Archaeologia 93 (1949), pp. 151-63

W. Rodwell and T. Tatton-Brown (eds.) Westminster: the art, architecture and archaeology of the Royal Abbey and Palace. British Archaeological Association Conference (39th: 2013: London) (Leeds 2015)

N. Saul, For Honour and Fame: Chivalry in England 1066-1500 (London: Vintage, 2011)

Alison Shell, Catholicism, Controversy and the English Literary Imagination, 1558–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)